Wednesday, 13 August 2025

Present with Go Modules

There are a few quite interesting utilities in the Go Tools collection, golang.org/x/tools.

One of these is the slide presentation software present.

$ go install golang.org/x/tools/cmd/present@latest

If you have watched any Go presentations in the past, there is quite a chance you have already seen present in action.

For example, many of Rob Pike’s talks are using present, e.g., his talk on lexical scanning.

present renders Markdown-ish files to either slides or articles - such as for the Go blog - to be displayed in a web browser.

Although the feature set is limited, one killer feature is the ability to execute code directly from the slides.

The golang.org/x/tools/present package describes the anatomy of a .slide input file and all available commands.

.play Some Code

The mentioned code execution killer feature is named .play and allows not only embedding code, but actually executing this code.

For example, the following line in a .slide file would display the content of some demo.go file, make the text box editable, and allow the code to be executed.

.play -edit demo.go

Earlier this year, I have used this for my “Privilege Separation In Go” talk at FOSDEM. At around the 02:00 mark in the linked talk, you can see me altered the code to demonstrate the privileges with which the code usually runs.

Later in the talk, I showed multiple Go libraries that I used directly within present.

This, however, was quite a hassle since present - being an older, not so official Go tool - still relies on the $GOPATH.

Since time was not on my side, I have ended up filling the $GOPATH manually.

And all this over six years after Go 1.11, deep in the age of Go Modules.

Since I was planning to work with external libraries in present again, I settled to patch it in this regard.

Just to find out that it can already do this.

.play Me A Go Module

The .play command works not only on Go code, but also on the txtar archive format, which I just learned about today (actually, it was yesterday - I am now finishing this post).

In a nutshell, it is a plain text format concatenating multiple text files, each being introduced by a -- FILENAME -- marker, with FILENAME being the actual file name.

There may also be a comment before the first file’s marker.

The .played file will be parsed as a txtar archive.

If the file is an ordinary Go source code file, there will be no marker and everything is part of the leading comment.

A non-empty comment will then be treated as a prog.go file.

However, if the input contains txtar entries, each one will be created.

Additionally, if a go.mod file is included in the txtar input, the Go code will be built as a Go Module.

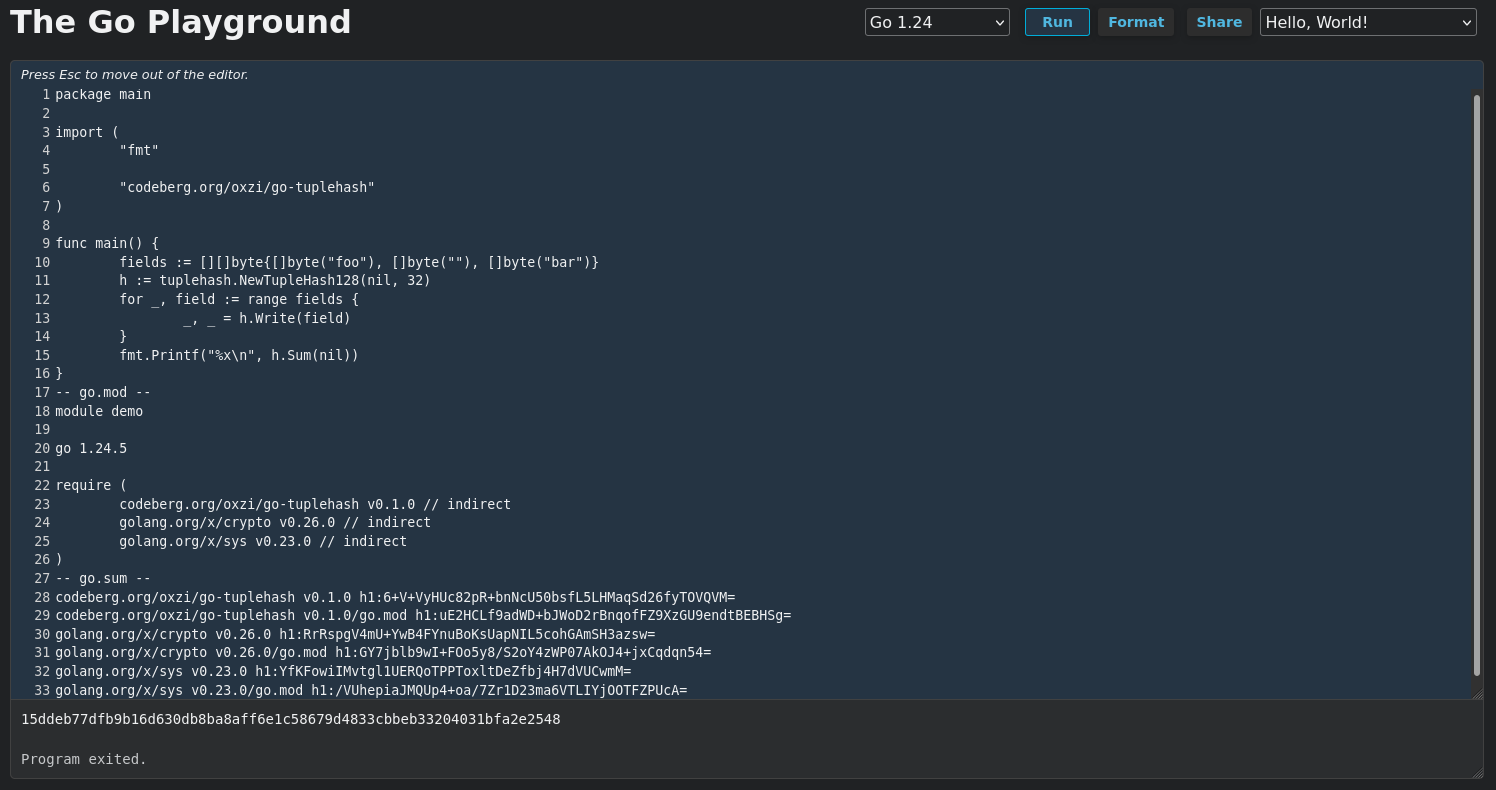

In practice, this looks like the following. For example’s sake, I am using the SHA-3 TupleHash library I wrote a while back.

$ go mod init demo

go: creating new go.mod: module demo

$ cat main.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"codeberg.org/oxzi/go-tuplehash"

)

func main() {

fields := [][]byte{[]byte("foo"), []byte(""), []byte("bar")}

h := tuplehash.NewTupleHash128(nil, 32)

for _, field := range fields {

_, _ = h.Write(field)

}

fmt.Printf("%x\n", h.Sum(nil))

}

$ go get codeberg.org/oxzi/go-tuplehash

[ . . . ]

$ go build

$ cp main.go demo.txtar

$ for f in go.{mod,sum}; do echo "-- $f --"; cat "$f"; done >> demo.txtar

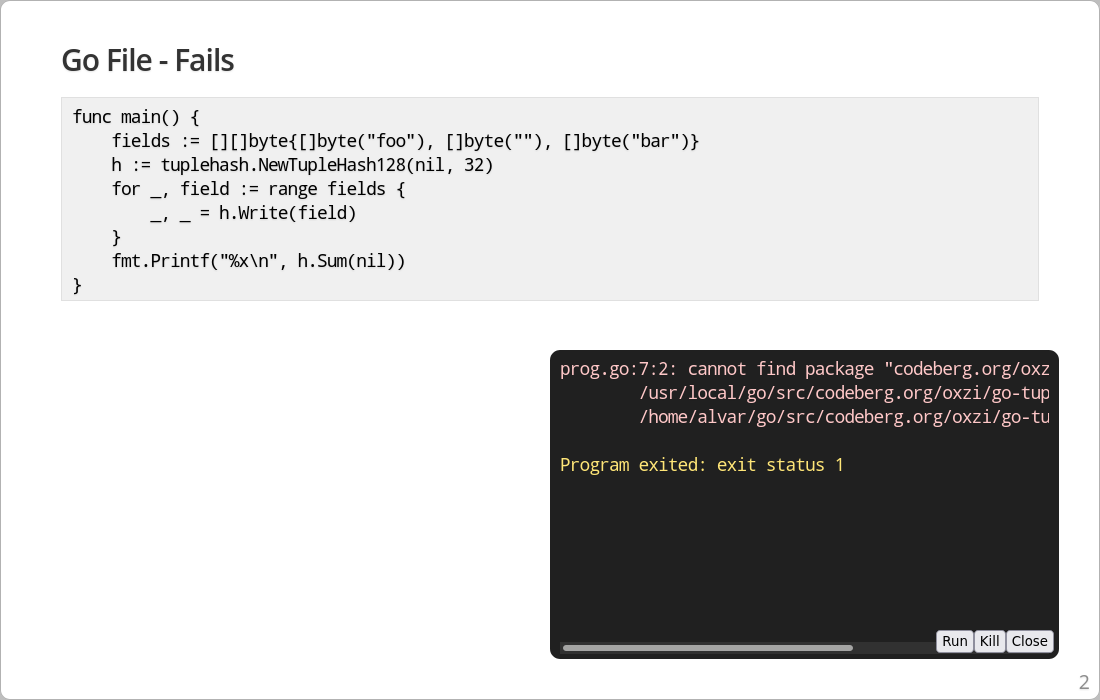

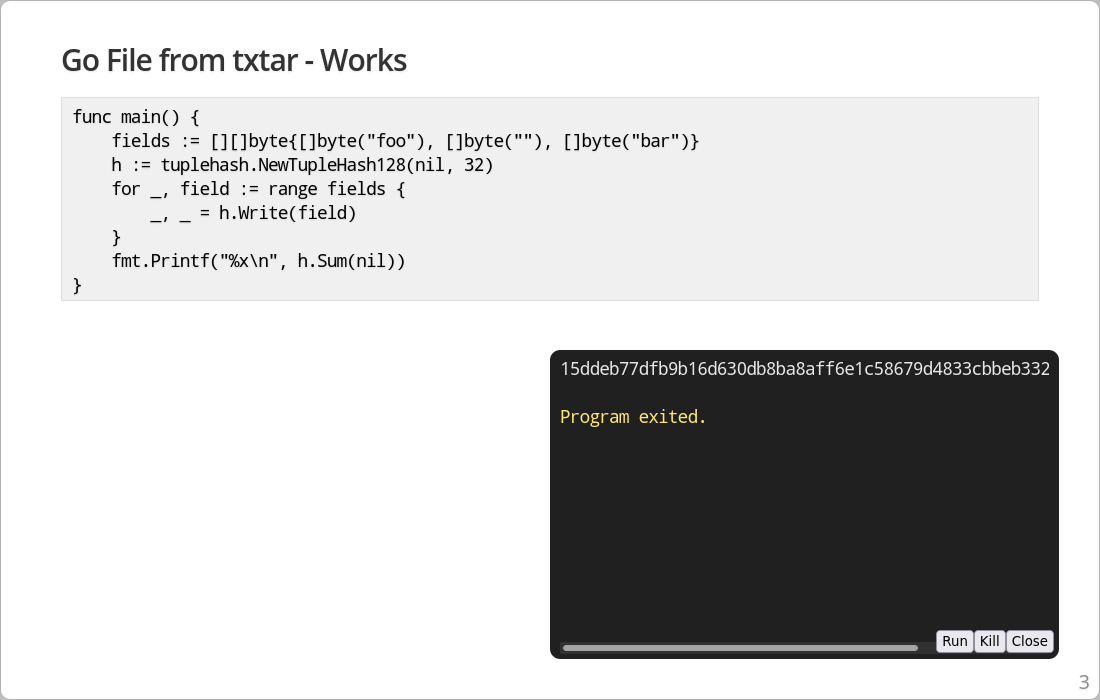

This can be demonstrated with a simple .slide file as follows.

The /^func main/,/^}/ part behind the .play calls reduces the printed output to the main function for aesthetic reasons.

# External Module Test

## Go File - Fails

.play main.go /^func main/,/^}/

## Go File from txtar - Works

.play demo.txtar /^func main/,/^}/

First, present fails due to missing packages - as expected.

The second example based on txtar works and produces a hopefully valid output.

.play Me Any Script

While poking through the playground socket code, I made another unexpected discovery: shebang support!

If the code starts with a shebang (#!), then it will not be compiled as a Go application, but executed by the shebang interpreter.

Therefore, present can be used to run almost any code.

Let’s demonstrate this with an even simpler example of the following .slide:

# Shebang Test

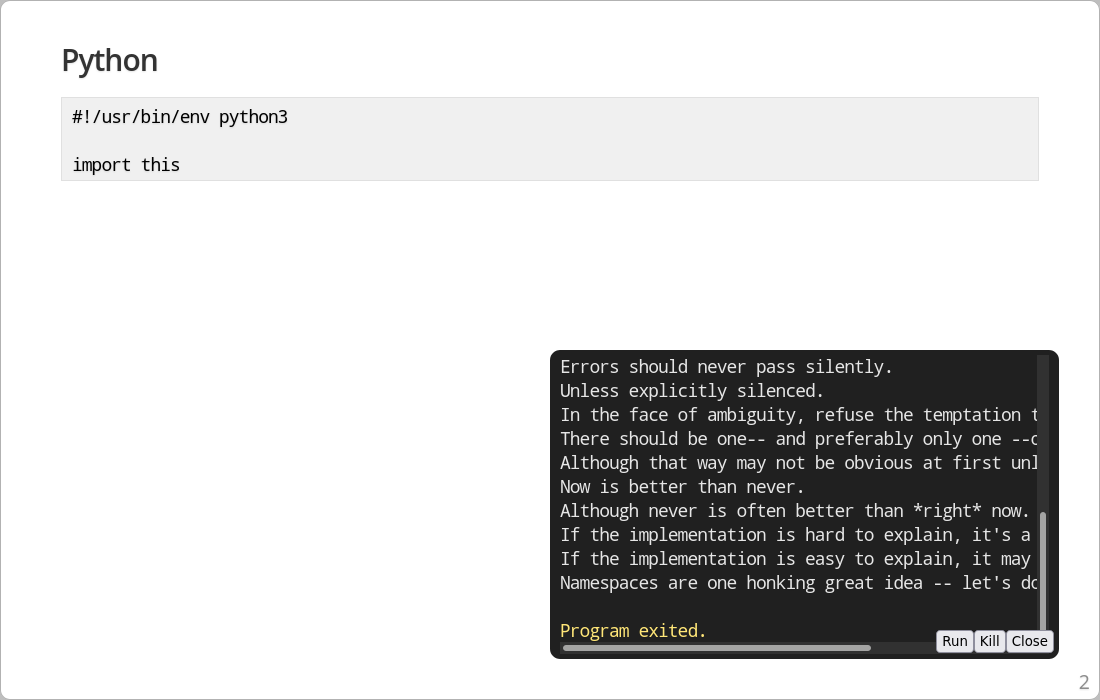

## Python

.play -edit demo.py

And demo.py looking like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import this

present executing a Python script running the PEP 20 easter egg.

Swimming Upstream Is Hard

First and foremost, a random blog post should not be the place to document implementation behavior. Documentation should be, well, in the docs. I have created a pull request, so let’s see how it turns out.

Google’s contribution maze for Go typically guides one through their Gerrit code review tool.

Last time I have used it was roughly two years ago and, of course, it requires a Google account.

And this was also the last time I have used my Google account, which still has a @googlemail.com address instead of @gmail.com.

What’s my age again?

When I tried to log in to this account, Google blocked the login because it thought there was something suspicious about me. As so called “options” to unblock the account, I should either use the same device or a similar location as last time - I have moved roughly 300km. That’s all, no other options.

No Gerrit for me today. This is just another downsides of big tech FOSS projects.

It’s Not A Bug, It’s A Feature

When people ask me what I like about Go, I usually mention its well documented API.

As being part of the /x/ namespace, the Go Tools are not so official, but once I became accustomed to the high quality documentation, their lack stood out.

And in this case, it misses two very special cases of executing code.

Taking a look at the txtar extraction logic is also a bit scary.

Yes sir, I would like you to extract ../../../../../etc/passwd.

This has only no further security implications as arbitrary user-supplied code will be executed next.

Thus, do not let present run wild and only execute trusted .slides.

Speaking of undocumented behavior, I tried the same thing in the Go Playground and was quite surprised that the txtar trick worked there as well.

Unlike the other code, the Go Playground has some input sanitation in place.

Unfortunately, there seems to be no shebang support.

Go Module in the Go Playground as txtar encoded input.

All The Negativity?

The last two sections turned out quite bitter, and I failed to find a way to change that.

However, I wanted to end on a positive note and emphasize one more time that I really enjoy working with present.

It is a fantastic tool, especially for presentations with code.

Use it!

Saturday, 09 August 2025

Rigging-suspended installation of a marine wind generator

We cruise on a small boat, a 31ft double-ender. As we’re off-grid the vast majority of the time, all electricity needs to be produced from renewable sources. Solar produces a lion’s share, but other sources are needed for overcast days. We don’t have space for a permanently mounted wind generator, so we converted a Superwind 350 to rigging-suspended.

Why wind?

As our 2024 cruise to the not-so-sunny Scotland demonstrated, there would still be place for wind power in the renewables mix of a long-distance sailboat. My energy production simulations from 2023 also showed a lot of promise for wind power.

Our boat has a canoe stern and dual aft stays, meaning that there is not much space in the back of the boat. We had a conversation with Superwind back in 2022, and they were of the opinion that there simply isn’t a good space for installing one. And so we installed a hydrogenerator and decided that we’d go sailing if we ran out of power.

But the interest in wind generators remained.

And then one day, rowing around the Sainte-Anne anchorage in rainy Martinique, I saw a potential solution: one of the small cruising boats had a wind generator suspended from ropes in their foretriangle. I chatted a bit with the owners, and they confirmed that the system worked nicely. Time for some research!

Rigging-suspended wind generator

Rigging-suspended wind generators used to be common. Commercial models included the Ampair 100, WindBugger, and the Hamilton-Ferris. As solar power has become cheaper, wind generators in general have fallen out of favor. At the same time cruising boats have grown in size, enabling permanent mounting of a big wind turbine.

These effects combined mean that there are currently no commercial manufacturers of rigging-suspended wind generators for boats.

Of the models once manufactured, the Ampair 100 sounded especially promising. It was a modular system that could be used either as a rigging-suspended wind turbine, or as a “tow generator” for making power while under sail.

This modularity is a big advantage of a rigging-suspended wind generator, especially for ease of stowing. They can also be a lot quieter than the pole-mounted ones, as any vibrations are dampened by the suspension ropes. And of course they don’t cause any windage or shading while stowed.

I tried finding an Ampair for sale online with no luck. The second-hand chandlery in Grenada – Treasure Trove – had two units, but couldn’t locate the wind blades.

However, the wind generator market has evolved quite a bit. There are several good wind generators intended for permanent mounting. Superwind and the D400 provide the best alternatives, but are very expensive. On the cheap end, there are numerous Chinese wind generators from companies like Pikasola and Vevor starting at around $250.

Maybe I could design a bracket to convert one of these for rigging-suspended installation?

Building the bracket

Sitting in the windy anchorage at Spanish Water this idea started sounding more and more interesting. After some paper brainstorming, I grabbed FreeCAD and made an initial design.

The design parameters were:

- Can be built somewhat cheaply by a local metal fabricator

- Can facilitate the most common fixed-mount wind generators

- Poles to keep the rigging lines clear of the propellers

- Wind generator is held in place and the whole assembly turns into the wind

My original idea was a neat stainless ring around the wind generator body. However, different wind generators are of different height, and so in interests of both manufacturing cost and adaptability, I went with two brackets connected by threaded rod.

It took a couple of months to actually get a quote from a local fabricator, but now we finally have the finished brackets for ourselves and a neighboring boat.

You can find the FreeCAD file on GitHub. There are also STEP files for the top bracket and the bottom bracket.

Installation

Our neighbor installed a 400W Pikasola wind generator on theirs. That mounted on the bracket without any other adapting except for some rubber mat to isolate the stainless parts from the aluminium wind turbine body.

We had bought an old Superwind 350 from another boat, and so for us a small connecting piece (140mm long aluminium pipe with 55mm inner diameter) was needed to make that fit.

The wind generator is hoisted using our spinnaker pole topping lift, with a short strop riding on the inner forestay. Stabilization is with a three rope bridle connected to pad eyes on the deck.

We have wires running from the bottom bracket to the deck level, where they connect via MC4 connectors to to cables running to inside the boat. This way we can easily disconnect the wind turbine as needed. We are adding a stop/run switch soon as well to aid deployment.

Deployment is already documented in our boat handbook.

Conclusion

We only got the Superwind deployed yesterday evening, and so we are gathering the early experiences. However, right now we’re on track to producing about 0.6kWh on the first day. This is measured with a dedicated Victron SmartShunt wired to the wind generator regulator and logging into our time series database.

That 0.6kWh per day is like a whole second solar arch!

Noise levels are not too bad at all. Inside the boat you can’t hear anything. In cockpit, you can hear a slight whirr from the generator, but it is a lot quieter than one of the popular pole-mounted wind turbines on neighboring boat, heard from few hundred meters away.

Durability and handling of heavier winds will remain to be seen. As will the practicality of stowing and deploying when changing anchorages. Though we already do similar things with the mast-hoisted solar panels and the nesting dinghy.

Especially when going with one of the cheap Chinese models, this rigging-suspended method can be the way to add wind power to a boat in an affordable way. We calculated the total price for the Pikasola installation to be around the same as what marine wind generator manufacturers ask for just a mounting pole!

The hardware design should be quite easy to manufacture anywhere where you can find a stainless steel welder. After all, we were able to get ours fabricated on a tropical island.

For us the new wind generator can be seen as completing the circle of our deployable renewable options:

- When under sail, power is generated with the hydrogenerator

- When anchored in light winds, power is generated with the mast-hoisted FLINsail solar array

- When anchored in heavier winds, power is generated by the rigging-suspended Superwind

On top of these we have the fixed solar panels.

Tuesday, 05 August 2025

Common Threads of Computer Company History

When descending into the vaults of computing history, as I have found myself doing in recent years, and with the volume of historical material now available for online perusal, it has largely become possible to finally have the chance of re-evaluating some of the mythology cultivated by certain technological communities, some of it dating from around the time when such history was still being played out. History, it is said, is written by the winners, and this is true to a large extent. How often have we seen Apple being given the credit for many technological developments that were actually pioneered elsewhere?

But the losers, if they may be considered that, also have their own narratives about the failure of their own favourites. In “A Tall Tale of Denied Glory”, I explored some myths about Commodore’s Amiga Unix workstation and how it was claimed that this supposedly revolutionary product was destined for success, cheered on by the big names in workstation computing, only to be defeated by Commodore’s own management. The story turned out to be far more complicated than that, but it illustrates that in an earlier age where there was more limited awareness of an industry with broader horizons than many could contemplate, everyone could get round a simplistic tale and vent their frustration at the outcome.

Although different technological communities, typically aligned with certain manufacturers, did interact with each other in earlier eras, even if the interactions mostly focused on advocacy and argument about who had chosen the best system, there was always the chance of learning something from each other. However, few people probably had the opportunity to immerse themselves in the culture and folklore of many such communities at once. Today, we have the luxury of going back and learning about what we might have missed, reading people’s views, and even watching television programmes and videos made about the systems and platforms we just didn’t care for at the time.

It was actually while searching for something else, as most great discoveries seem to happen, that I encountered some more mentions of the Amiga Unix rumours, these being relatively unremarkable in their familiarity, although some of them were qualified by a claim by the person airing these rumours (for the nth time) that they had, in fact, worked for Sun. Of course, they could have been the mailboy for all I know, and my threshold for authority in potential source material for this matter is now set so high that it would probably have to be Scott McNealy for me to go along with these fanciful claims. However, a respondent claimed that a notorious video documenting the final days of Commodore covered the matter.

I will not link to this video for a number of reasons, the most trivial of which is that it just drags on for far too long. And, of course, one thing it does not substantially cover is the matter under discussion. A single screen of text just parrots the claims seen elsewhere about Sun planning to “OEM” the Amiga 3000UX without providing any additional context or verification. Maybe the most interesting thing for me was to see that Commodore were using Apollo workstations running the Mentor Graphics CAD suite, but then so were many other companies at one point in time or other.

In the video, we are confronted with the demise of a company, the accompanying desolation, cameraderie under adversity, and plenty of negative, angry, aggressive emotion coupled with regressive attitudes that cannot simply be explained away or excused, try as some commentators might. I found myself exploring yet another rabbit hole with a few amusing anecdotes and a glimpse into an era for which many people now have considerable nostalgia, but one that yielded few new insights.

Now, many of us may have been in similar workplace situations ourselves: hopeless, perhaps even deluded, management; a failing company shedding its workforce; the closure of the business altogether. Often, those involved may have sustained a belief in the merits of the enterprise and in its products and people, usually out of the necessity to keep going, whether or not the management might have bungled the company’s strategy and led it down a potentially irreversible path towards failure.

Such beliefs in the company may have been forged in earlier, more successful times, as a company grows and its products are favoured over those of the competition. A belief that one is offering something better than the competition can be highly motivating. Uncalibrated against the changing situation, however, it can lead to complacency and the experience of helplessly watching as the competition recover and recapture the market. Trapped in the moment, the sequence of events leading to such eventualities can be hard to unravel, and objectivity is usually left as a matter for future observers.

Thus, the belief often emerges that particular companies faced unique challenges, particularly by the adherents of those companies, simply because everything was so overwhelming and inexplicable when it all happened, like a perfect storm making an unexpected landfall. But, being aware of what various companies experienced, and in peeking over the fence or around the curtain at what yet another company may have experienced, it turns out that the stories of many of these companies all have some familiar, common themes. This should hardly surprise us: all of these companies will have operated largely within the same markets and faced common challenges in doing so.

A Tale of Two Companies

The successful microcomputer vendors of the 1980s, which were mostly those that actually survived the decade, all had to transition from one product generation to the next. Acorn, Apple and Commodore all managed to do so, moving up from 8-bit systems to more sophisticated systems using 32-bit architectures. But these transitions only got them so far, both in terms of hardware capabilities and the general sophistication of their systems, and by the early 1990s, another update to their technological platforms was due.

Acorn had created the ARM processor architecture, and this had mostly kept the company competitive in terms of hardware performance in its traditional markets. But it had chosen a compromised software platform, RISC OS, on which to base its Archimedes systems. It had also introduced a couple of Unix workstation products, themselves based on the Archimedes hardware, but these were trailing the pace in a much more competitive market. Acorn needed the newly independent ARM company to make faster, more capable chips, or it would need embrace other processor architectures. Without such a boost forthcoming, it dropped Unix and sought to expand in “longshot” markets like set-top boxes for video-on-demand and network computing.

Commodore had a somewhat easier time of it, at least as far as processors were concerned, riding on the back of what Motorola had to offer, which had been good enough during much of the 1980s. Like Acorn, Commodore made their own graphics chips and had enjoyed a degree of technical superiority over mainstream products as a result, but as Acorn had experienced, the industry had started to catch up, leading to a scramble to either deliver something better or to go with the mainstream. Unlike Acorn, Commodore did do a certain amount of business actually going with the mainstream and selling IBM-compatible PCs, although the increasing commoditisation of that business led the company to disengage and to focus on its own technologies.

Commodore had its own distractions, too. While Acorn pursued set-top boxes for high-bandwidth video-on-demand and interactive applications on metropolitan area networks, Commodore tried to leverage its own portfolio rather more directly, trading on its strengths in gaming and multimedia, hoping to be the one who might unite these things coherently and lucratively. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Japanese games console manufacturers had embraced the Compact Disc format, but NEC’s PC Engine CD-ROM² and Sega’s Mega-CD largely bolted CD technology onto existing consoles. Philips and Sony, particularly the former, had avoided direct competition with games consoles, pitching their CD-i technology more at the rather more sedate “edutainment” market.

With CDTV, Commodore attempted to enter the same market at Philips, downplaying the device’s Amiga 500 foundations and fast-tracking the product to market, only belatedly offering the missing CD-ROM drive option for its best-selling Amiga 500 system that would allow existing customers to largely recreate the same configuration themselves. Both CD-i and CDTV were considered failures, but Commodore wouldn’t let go, eventually following up with one of the company’s final products, the CD32, aiming more directly at the console market. Although a relative success against the lacklustre competition, it came too late to save the company which had entered a steep decline only to be driven to bankruptcy by a patent aggressor.

Whether plucky little Commodore would have made a comeback without financial headwinds and patent industry predators is another matter. Early multimedia consoles had unconvincing video playback capabilities without full-motion video hardware add-ons, but systems like the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer sought to strengthen the core graphical and gaming capabilities of such products, introducing hardware-accelerated 3D graphics and high-quality audio. Within only a year or so of the CD32’s launch, more complete systems such as the Sega Saturn and, crucially, the Sony PlayStation would be available. Commodore’s game may well have been over, anyway.

Back in Cambridge, a few months after Commodore’s demise, Acorn entered into a collaboration with an array of other local technology, infrastructure and media companies to deliver network services offering “interactive television“, video-on-demand, and many of the amenities (shopping, education, collaboration) we take for granted on the Internet today, including access to the Web of that era. Although Acorn’s core technologies were amenable to such applications, they did need strengthening in some respects: like multimedia consoles, video decoding hardware was a prerequisite for Acorn’s set-top boxes, and although Acorn had developed its own competent software-based video decoding technology, the market was coalescing around the MPEG standard. Fortunately for Acorn, MPEG decoder hardware was gradually becoming a commodity.

Despite this interactive services trial being somewhat informative about the application of the technologies involved, the video-on-demand boom fizzled out, perhaps demonstrating to Acorn once again that deploying fancy technologies in a relatively affluent region of the country for motivated, well-served early adopters generally does not translate into broader market adoption. Particularly if that adoption depended on entrenched utility providers having to break open their corporate wallets and spend millions, if not billions, on infrastructure investments that would not repay themselves for years or even decades. The experience forced Acorn to refocus its efforts on the emerging network computer trend, leading the company down another path leading mostly nowhere.

Such distractions arguably served both companies poorly, causing them to neglect their core product lines and to either ignore or to downplay the increasing uncompetitiveness of those products. Commodore’s efforts to go upmarket and enter the potentially lucrative Unix market had begun too late and proceeded too slowly, starting with efforts around Motorola 68020-based systems that could have opened a small window of opportunity at the low end of the market if done rather earlier. Unix on the 68000 family was a tried and tested affair, delivered by numerous companies, and supplied by established Unix porting houses. All Commodore needed to do was to bring its legendary differentiation to the table.

Indeed, Acorn’s one-time stablemate, Torch Computers, pioneered low-end graphical Unix computing around the earlier 68010 processor with its Triple X workstation, seeking to upgrade to the 68020 with its Quad X workstation, but it had been hampered by a general lack of financing and an owner increasingly unwilling to continue such financing. Coincidentally, at more or less the same time that the assets of Torch were finally being dispersed, their 68030-based workstation having been under development, Commodore demonstrated the 68030-based Amiga 3000 for its impending release. By the time its Unix variant arrived, Commodore was needing to bring far more to the table than what it could reasonably offer.

Acorn themselves also struggled in their own moves upmarket. While the ARM had arrived with a reputation of superior performance against machines costing far more, the march of progress had eroded that lead. The designers of the ARM had made a virtue of a processor being able to make efficient use of its memory bandwidth, as opposed to letting the memory sit around idle as the processor digested each instruction. This facilitated cheaper systems where, in line with the design of Acorn’s 8-bit computers, the processor would take on numerous roles within the system including that of performing data transfers on behalf of hardware peripherals, doing so quite effectively and obviating the need for costly interfacing circuitry that would let hardware peripherals directly access the memory themselves.

But for more powerful systems, the architectural constraints can be rather different. A processor that is supposedly inefficient in its dealings with memory may at least benefit from peripherals directly accessing memory independently, raising the general utilisation of the memory in the system. And even a processor that is highly effective at keeping itself busy and highly efficient at utilising the memory might be better off untroubled by interrupts from hardware devices needing it to do work for them. There is also the matter of how closely coupled the processor and memory should be. When 8-bit processors ran at around the same speed as their memory devices, it made sense to maximise the use of that memory, but as processors increased in speed and memory struggled to keep pace, it made sense to decouple the two.

Other RISC processors such as those from MIPS arrived on the market making deliberate use of faster memory caches to satisfy those processors’ efficient memory utilisation while acknowledging the increasing disparity between processor and memory speeds. When upgrading the ARM, Acorn had to introduce a cache in its ARM3 to try and keep pace, doing so with acclaim amongst its customers as they saw a huge jump in performance. But such a jump was long overdue, coming after Acorn’s first Unix workstation had shipped and been largely overlooked by the wider industry.

Acorn’s second generation of workstations, being two configurations of the same basic model, utilised the ARM3 but lacked a hardware floating-point unit. Commodore could rely on the good old 68881 from Motorola, but Acorn’s FPA10 (floating-point accelerator) arrived so late that only days after its announcement, three years or so after those ARM3-based systems had been launched and two years later than expected, Acorn discontinued its Unix workstation effort altogether.

It is claimed that Commodore might have skipped the 68030 and gone straight for the 68040 in its Unix workstation, but indications are that the 68040 was probably scarce and expensive at first, and soon only Apple would be left as a major volume customer for the product. All of the other big Motorola 68000 family customers had migrated to other architectures or were still planning to, and this was what Commodore themselves resolved to do, formulating an ambitious new chipset called Hombre based around Hewlett-Packard’s PA-RISC architecture that was never realised.

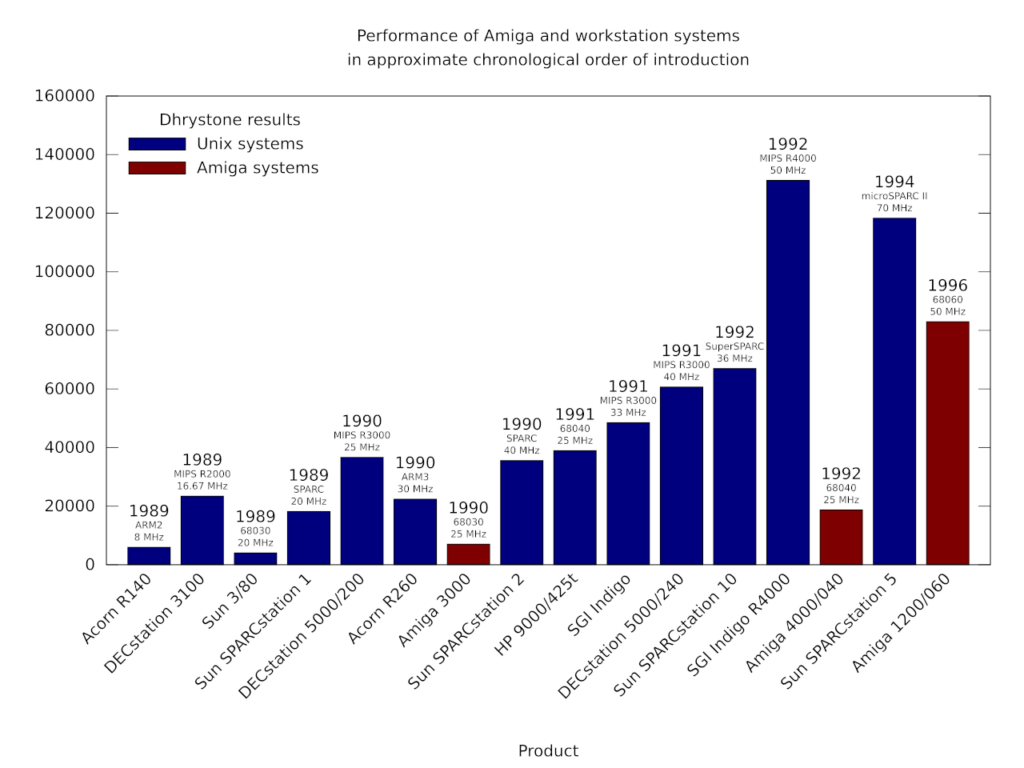

A chart showing how Unix workstation performance steadily improved, largely through the introduction of steadily faster RISC processors. Note how the HP 9000/425t gets quite impressive performance from the 68040. Even a system introduced with a 68060 straight off the first production run in 1994 would have been up against fearsome competition. Worth mentioning is that Acorn’s R140, although underpowered, was a low-cost colour workstation running Unix and the X Window System.

Acorn, meanwhile, finally got a chip upgrade from ARM in the form of the rather modest ARM6 series, choosing to develop new systems around the ARM600 and ARM610 variants, along with systems using upgraded sound and video hardware. One additional benefit of the newer ARM chips was an integrated memory management unit more suitable for Unix implementations than the one originally developed for the ARM. For followers of the company, such incoming enhancements provided a measure of hope that the company’s products would remain broadly competitive in hardware terms with mainstream personal computers.

Perhaps most important to most Acorn users at the time, given the modest gains they might see from the ARM600/610, was the prospect of better graphical capabilities, but Acorn chose not to release their intermediate designs along the way to their grand new system. And so, along came the Risc PC: a machine with two processor sockets and logic to allow one of the processors to be an x86-compatible processor that could run PC software. Once again, Acorn gave the whole hardware-based PC accelerator card concept another largely futile outing, failing to learn that while existing users may enjoy dabbling with software from another platform, it hardly ever attracts new customers in any serious numbers. Even Commodore had probably learned that lesson by then.

Nevertheless, Acorn’s Risc PC was a somewhat credible platform for Unix, if only Acorn hadn’t cancelled their own efforts in that realm. Prominent commentators and enthusiastic developers seized the moment, and with Free Software Unix implementations such as NetBSD and FreeBSD emerging from the shadow of litigation cast upon them, a community effort could be credibly pursued. Linux was also ported to ARM, but such work was actually begun on Acorn’s older A5000 model.

Acorn never seized this opportunity properly, however. Despite entering the network computer market in pursuit of some of Larry Ellison’s billions, expectations of the software in network computers had also increased. After all, networked computers have many of the responsibilities of those sophisticated minicomputers and workstations. But Acorn was still wedded to RISC OS and, for the most part, to ARM. And it ultimately proved that while RISC OS might present quite a nice graphical interface, it was actually NetBSD that could provide the necessary versatility and reliability being sought for such endeavours.

And as the 1990s got underway, the mundane personal computer started needing some of those workstation capabilities, too, eventually erasing the distinction between these two product categories. Tooling up for Unix might have seemed like a luxury, but it had been an exercise in technological necessity. Acorn’s RISC OS had its attractions, notably various user interface paradigms that really should have become more commonplace, together with a scalable vector font system that rendered anti-aliased characters on screen years before Apple or Microsoft managed to, one that permitted the accurate reproduction of those fonts on a dot-matrix printer, a laser printer, and everything in-between.

But the foundations of RISC OS were a legacy from Acorn’s 8-bit era, laid down hastily in an arguably cynical fashion to get the Archimedes out of the door and to postpone the consequences. Commodore inevitably had similar problems with its own legacy software technology, ostensibly more modern than Acorn’s when it was introduced in the Amiga, even having some heritage from another Cambridge endeavour. Acorn might have ported its differentiating technologies to Unix, following the path taken by Torch and its close relative, IXI, also using the opportunity to diversify its hardware options.

In all of this consideration given to Acorn and Commodore, it might seem that Apple, mentioned many paragraphs earlier, has been forgotten. In fact, Apple went through many of the same trials and ordeals as its smaller rivals. Indeed, having made so much money from the Macintosh, Apple’s own attempts to modernise itself and its products involve such a catalogue of projects and initiatives that even summarising them would expand this article considerably.

Only Apple would buy a supercomputer to attempt to devise its own processor architecture – Aquarius – only not to follow through and eventually be rescued by the pair of IBM and Motorola, humbled by an unanticipated decline in their financial and market circumstances. Or have several operating system projects – Opus, Pink, Star Trek, NuKernel, Copland – that were all started but never really finished. Or to get into personal digital assistants with the unfairly maligned Newton, or to consider redesigning the office entirely with its Workspace 2000 collaboration. And yet end up acquiring NeXT, revamping its technologies along that company’s lines, and still barely make it to the end of the decade.

The Final Chapters

Commodore got almost half-way through the 1990s before bankruptcy beckoned. Motorola’s 68060, informed by the work on the chip manufacturer’s abandoned 88000 RISC architecture, provided a considerable performance boost to its more established architecture, even if it now trailed the pack, perhaps only matching previous generations of SPARC and MIPS processors, and now played second fiddle to PowerPC in Motorola’s own line-up.

Acorn’s customers would be slightly luckier. Digital’s StrongARM almost entirely eclipsed ARM’s rather sedate ARM7-based offerings, except in floating-point performance in comparison to a single system-on-chip product, the ARM7500FE. This infusion of new technology was a blessing and a curse for Acorn and its devotees. The Risc PC could not make full use of this performance, and a new machine would be needed to truly make the most of it, also getting a long-overdue update in a range of core industry technologies.

Commodore’s devotees tend to make much of the company’s mismanagement. Deserved or otherwise, one may now be allowed to judge whether the company was truly unique in this regard. As Acorn’s network computer ambitions were curtailed, market conditions became more unfavourable to its increasingly marginalised platform, and the lack of investment in that core platform started to weigh heavily on the company and its customers. A shift in management resulted in a shift in business and yet another endeavour being initiated.

Acorn’s traditional business units were run down, the company’s next generation of personal computer hardware cancelled, and yet a somewhat tangential silicon design business was effectively being incubated elsewhere within the organisation. Meanwhile, Acorn, sitting on a substantial number of shares in ARM, supposedly presented a vulnerability for the latter and its corporate stability. So, a plan was hatched that saw Acorn sold off to a division of an investment bank based in a tax haven, the liberation of its shares in ARM, and the dispersal of Acorn’s assets at rather low prices. That, of course, included the newly incubated silicon design operation, bought by various figures in Acorn’s “senior management”.

Just as Commodore’s demise left customers and distributors seemingly abandoned, so did Acorn’s. While Commodore went through the indignity of rescues and relaunches, Acorn itself disappeared into the realms of anonymous holding companies, surfacing only occasionally in reports of product servicing agreements and other unglamorous matters. Acorn’s product lines were kept going for as long as could be feasible by distributors who had paid for the privilege, but without the decades of institutional experience of an organisation terminated almost overnight, there was never likely to be a glorious resurgence of its computer systems. Its software platform was developed further, primarily for set-top box applications, and survives today more as a curiosity than a contender.

In recent days, efforts have been made by Commodore devotees to secure the rights to trademarks associated with the company, these having apparently been licensed by various holding companies over the years. Various Acorn trademarks were also offloaded to licensors, leading to at least one opportunistic but ill-conceived and largely unwelcome attempt to trade on nostalgia and to cosplay the brand. Whether such attempts might occur in future remains uncertain: Acorn’s legacy intersects with that of the BBC, ARM and other institutions, and there is perhaps more sensitivity about how its trademarks might be used.

In all of this, I don’t want to downplay all of the reasons often given for these companies’ demise, Commodore’s in particular. In reading accounts of people who worked for the company, it is clear that it was not a well-run workplace, with exploitative and abusive behaviour featuring disturbingly regularly. Instead, I wish to highlight the lack of understanding in the communities around these companies and the attribution of success or failure to explanations that do not really hold up.

For instance, the Acorn Electron may have consumed many resources in its development and delivery, but it did not lead to Acorn’s “downfall”, as was claimed by one absurd comment I read recently. Acorn’s rescue by Olivetti was the consequence of several other things, too, including an ill-advised excursion into the US market, an attempt to move upmarket with an inadequate product range, some curious procurement and logistics practices, and a lack of capital from previous stock market flotations. And if there had been such a “downfall”, such people would not be piping up constantly about ARM being “the chip in everyone’s phone”, which is tiresomely fashionable these days. ARM may well have been just a short footnote in some dry text about processor architectures.

In these companies, some management decisions may have made sense, while others were clearly ill-considered. Similarly, those building the products could only do so much given the technological choices that had already been made. But more intriguing than the actual intrigues of business is to consider what these companies might have learned from each other, what the product developers might have borrowed from each other had they been able to, and what they might have achieved had they been able to collaborate somehow. Instead, both companies went into decline and ultimately fell, divided by the barriers of competition.

Thursday, 31 July 2025

Stop Killing Games

Updated on the 31st of July to reflect the fact deadline for both petitions have now passed.

The dystopian interpretation of the ‘you’ll own nothing and be happy’ phrase feels increasingly prescient.1 As corporations hide behind lengthy Terms of Service and End User License Agreements,2 the concept of ownership becomes alarmingly ambiguous. This erosion of consumer rights has given rise to the Stop Killing Games (SKG) movement.

In 2015 I’ve stumbled upon the Classic Tetris World Championship. Even though I’d never played NES Tetris, I started following the event with interest. I keenly remember watching the historic 2018 final which was a prelude to the next generation of players picking up the game.

In contrast, world of racing games offer an example of fleeting ownership. While generations continue to enjoy NES Tetris, with a 13-year-old famously ‘beating’ the game 34 years after its release,3 Ubisoft’s 2014 game The Crew didn’t even last a decade. In 2024, Ubisoft didn’t just shut down the servers; it began revoking players’ licenses, seemingly doing everything in its power to ensure the game couldn’t be preserved or revived by the community.

Customer rights

Even if you don’t care about video games, SKG is an important cause worth the few minutes needed to sign. The way I see it, this isn’t just about games, since the practices in the gaming industry are setting a dangerous precedent for other products.

Imagine if a developer could enter your house and take away a disk with professional software that your livelihood depends on. Or if a publisher could rip away a copy of your favourite novel from your shelf (cf. Amazon’s licensing debacle). Or if a hardware manufacturer could remotely brick your device without giving a reason. It’s quite easy to imagine, considering that things like that already happen. Just recently, Nintendo got into hot water for its ability to brick users’ Switch 2 consoles.

If this model of revoking access to purchased products finds no opposition in the world of video games, it’ll inevitably spread to other forms of digital content and even physical products with digital components. The SKG initiative is not just about games; it’s a stand against a future where our ownership is conditional. If we don’t act now, we may wake up in a Black Mirror episode.

The initiative

The goal of SKG is a world where once a customer buys a game, they own its copy and can continue playing it even if the publisher loses interest in it. The movement initiated two petitions:

- the European Citizen’s Initiative which has since ended with 1.4 million signatures; and

- the UK Government and Parliament petition which has since ended with nearly 190 thousand signatures.

Those are not symbolic Internet petitions; they are a part of a legislative process. Their goal has been reached since writing of this article, which forces a) a formal responses from the European Commission and b) a debated about the issue in the UK Parliament.

They experienced a dramatic rise in the number of petitioners recently. On the 2nd of July, the UK petition reached its goal of one hundred thousand signatures; a day later, the EU initiative reached its goal of one million signatures. However, there are still reasons to sign.

Ensuring validity

A buffer of signatures is needed to account for any that may be deemed invalid during official verification process.

Sending a message

Politicians and especially game publishers are watching. The greater the number of signatures, the clearer it is people are serious about the issue. Contrary to popular belief, vocal customers can affect change. Even if neither EU nor UK governments enact any new laws, game publishers may still think twice before implementing anti-customer features.

Broader support

For the EU initiative, reaching individual signature thresholds in all 27 member states would signify a pan-European unity on the issue. For that to happen we need more signatures from Malta, Cyprus and Luxembourg in particular.

1 It’s worth noting that the phrase is somewhat misunderstood. There was never an agenda to make it a reality but rather observation that things seem to move towards a world where everything is a service. With a view of how such future might look, it brought discussion of ownership to the forefront. ↩

2 Michael Karanicolas. 2021. Too Long; Didn't Read: Finding Meaning in Platforms’ Terms of Service Agreements. University of Toledo Law Review, Vol. 52, No. 1, 2021. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3887753 ↩

3 Historically, level 29 of NES Tetris was considered the kill screen because people could not keep up with game’s speed at that level. However, as younger generation of players got involved, new playing techniques were developed and beating level 29 became the norm. Eventually, Blue Scuti reaching level 157 and crashing the game therefore ‘beating’ Tetris. See aGameScout’s video for more detailed description. ↩

Sunday, 13 July 2025

Be My Guest at DSN 2025

I’m delighted to share my paper I’ve presented at the IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems: ‘Be My Guest: Welcoming Interoperability into IBC-Incompatible Blockchains’.

It introduces the concept of a guest blockchain which runs on top of a blockchain and provides features necessary to support the Inter-Blockchain Communication (IBC) protocol. This enables trustless cross-chain interoperability between blockchains which would otherwise not support IBC-based communication. We demonstrate our approach by deploying the guest blockchain on Solana connecting it to the Cosmos ecosystem with performance comparable to native IBC implementations.

Neapolitan heat notwithstanding, the conference was captivating with papers on variety of fascinating subjects. Naturally, AI was a popular topic. For example, Stephan Kleber talked about transferability of adversarial patches1 and Marta Kwiatkowska discussed provably correct autonomous systems. I’ve previously written about AI risks and it becomes apparent that relying on neural networks alone is insufficient for safety-critical systems.

Alas, I digress. After tumultuous history, ‘Be My Guest’ paper is now available together with the conference slides:

- IEEE Xplore entry

- The accepted paper (PDF, 286 k)

- Conference slides (PDF, 410 k)

This work is related to my articles about the Solana runtime. They describe limitations I had to content with when implementing the Solana IBC bridge:

1 Stephan Kleber, Jeremias Eppler, Tim Palm, Dennis Eisermann, and Frank Kargl. 2025. Assessing the Transferability of Adversarial Patches in Real-World Systems: Implications for Adversarial Testing of Image Recognition Security. In 55th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks – Supplemental Volume (DSN-S), Naples, Italy, 42–47. doi:10.1109/DSN-S65789.2025.00040 ↩

Saturday, 05 July 2025

KDE Gear 25.08 branches created

Make sure you commit anything you want to end up in the KDE Gear 25.08

releases to them

Next Dates:

- July 10 2025: 25.08 Freeze and Beta (25.07.80) tag & release

- July 24 2025: 25.08 RC (25.07.90) Tagging and Release

- August 7 2025: 25.08 Tagging

- August 14 2025: 25.08 Release

Wednesday, 25 June 2025

KDE will drop Qt5 CI Support at the End of September 2025

If you are a developer and your KDE project is still based on Qt5 you should really really start porting to Qt6 now.

https://mail.kde.org/pipermail/kde-devel/2025-June/003742.html

Tuesday, 24 June 2025

On publishing Ada & Zangemann in Danish

I and Øjvind started working in the Danish translation of Ada & Zangemann in 2023, Øjvind as translator and myself as proofreader.

Throughout 2024, we tried pitching the book to a number of Danish publishing houses, to no avail: Some didn’t respond, others didn’t want to publish the book.

In order to get an idea of what it would take to just print it, we got a quote from the Danish printing house LaserTryk, and it seemed OK: About DKK 40,000 for 1,000 copies or DKK 52,000 for 2,000 (note: 1 DKK ~0.13€, i.e. 1€ ~ 7.5 DKK). We briefly entertained the idea of doing print on demand only but quickly dismissed the idea: It’s difficult for a book that’s print on demand only and doesn’t go through the whole publishing cycle the way a “real” printed book does to have the same kind of cultural impact. And of course we’d like this book to have the maximum cultural impact possible.

And yet, the only remaining option seemed to publish it ourselves. So I registered a company with the Danish authorities, and we – I, Nico, Øjvind and Matthias – started work on the production of the printable PDF.

In order to raise money for paying the printing bill and various other expenses, I did the following:

- I gave the newly formed company a loan of DKK 60,000 (~8,000€) from my own savings

- I contacted various organizations about buying copies of the book to support. Notably, PROSA (the IT worker’s union, who have often supported free software initiatives) pledged to buy 100 copies. The companies Magenta and Semaphor also pledged to buy some copies.

We also contacted the children’s coding charity Coding Pirates who bought a box (33 copies) to sell on their web shop.

This advance sales almost covered half the printing bill (we ended up printing 2,000 copies).

The next step was to tell people about the book. We did this, among other things, by having a premiere for the Danish edition of the Ada & Zangemann film on March 27; by posting on Maston etc., and by having an official book launch on June 16.

We also sent review copies to various newspapers, and we submitted two copies to the Danish National Bibliography.

By doing that, we ensured that the book was considered for purchase by the public libraries. This in fact resulted in the book getting a healthy recommendation.

A good friend who is a self-published author himself adviced me to get a deal with a distributor – that would mean the book is available on the portal all booksellers use to order books, and that the distributor can handle all the necessary shipping. Such an agreement is not free of charge (of course), but on the other hand they will send any proceeds from sales to bookstores and libraries on a monthly basis with no extra work for the publisher.

So, how does it look now that the book has been published?

So far, ~250 copies have been sold, either through advance sales (as noted) or to individuals paying directly to me. From this, I received money enough for the company to repay me DKK 30,000 in early May. The company at the time of writing holds about DKK 20,000 but also owes the tax authorities about DKK 6,500 which will be paid later in June.

All in all, subtracting some storage expenses the deal may be some DKK 20,000 in the red – i.e., I still need to make about DKK 20,000 to break even.

The FSFE has pledged to buy some copies, and that, combined with the money I expect to come in soon from sales in book stores and to libraries, should ensure the numbers will become black soon. Once the remaining DKK 20,000 have been repaid to my savings, the company must pay its own way.

So, as I said: When the actual sales to libraries etc. start, the numbers should start becoming black. When that happens, the company can reinvest, e.g. gifting books to schools to raise awareness of the book, etc.

Just for possible inspiration – self-publishing is kind of doable in that way. What’s important, if you wish to use this procedure in your own country, is to use the existing professional infrastructure for book publishing: Distributors, library reviewers etc., and thankfully I had good help with that.

Sunday, 15 June 2025

KDE Gear 25.08 release schedule

This is the release schedule the release team agreed on

https://community.kde.org/Schedules/KDE_Gear_25.08_Schedule

Dependency freeze is in around 2 weeks (July 3) and feature freeze one

after that. Get your stuff ready!

A tale of two pull requests: Addendum

In the previous post, I criticised Rust’s contribution process, where a simple patch languished due to communication hurdles. Rust isn’t unique in struggling with its process. This time, the story is about Python.

Parsing HTML in Python

As its name implies, the html.parser module provides interfaces for parsing HTML documents. It offers an HTMLParser base class users can extend to implement their own handling of HTML markup. Of our interest is the unknown_decl method, which ‘is called when an unrecognised declaration is read by the parser.’ It’s called with an argument containing ‘the entire contents of the declaration inside the <![...]> markup.’ For example:

from html.parser import HTMLParser

class MyParser(HTMLParser):

def unknown_decl(self, data: str) -> None:

print(data)

parser = MyParser()

parser.feed('<![if test]>')

# Prints out: if test

# (unless Python 3.13.4+, see below)

parser.feed('<![CDATA[test]]>')

# Prints out: CDATA[testNotice the problem? When used with a CDATA declaration, the behavior doesn’t quite match the documentation: the argument passed to unknown_decl is missing a closing square bracket. This behaviour makes a simple task unexpectedly difficult. An HTML filter — say one which sanitises user input — would risk corrupting the data by adding the wrong number of closing brackets.

In May 2021, I developed and submitted a fix for the issue. However, contributing to Python requires signing a Python Software Foundation contributor license agreement (CLA), which required an account on bugs.python.org website. The problem is: I never received the activation email.

Eventually, a few days after the submission, a bot tagged the pull request with ‘CLA signed’ label. That should imply that everything was in order, and the patch was ready to be reviewed and merged. Yet, a year later, the label was manually removed, leaving the PR in limbo with no explanation. Was the CLA signed or not? The system itself seemed to have no consistent answer.

Python 3.13.4

Python 3.13.4 came out last week and changed this particular corner of the codebase. CDATA handling is unchanged, but other declarations are now passed to the parse_bogus_comment method, which uses a different matching mechanism.

Ironically, while that solved a different issue users had, the documentation remains incorrect and the CDATA handling is still bizarre (unknown_decl is called with unmatched square brackets) not to call it outright broken.

Discussion

I’m not fond of CLAs in the best of times, but if a project requires them, the least it could do is make sure that the system for getting them signed works correctly. It is surprising getting a physical paperwork for my Emacs contributions1 was easier than getting things done electronically for Python.

There were two differences: barrier to entry and someone to follow up on the signing process. To initiate contribution to Emacs, an email account is sufficient and sending a patch is enough to get the process started. In Python, there is upfront barrier of creating bugs.python.org account and signing the CLA.

Secondly, Emacs process had people involved ready to follow up. Any confusion I had was addressed, and — even though slow as it involved the post — it went smoothly. This was not the case in Python where there was no obvious way to contact someone about problems.

Ultimately, a thriving free software project needs not only quality code but also healthy community of contributors. Both Python and Rust are phenomenal technical achievements, but these stories show how even giants can stumble on human-scale issues.

1 It is my understanding that GNU projects which require copyright assignment offer an electronic process now. ↩

On a tale of two pull requests

I was going to leave a comment on “A tale of two pull requests”, but would need to authenticate myself via one of the West Coast behemoths. So, for the benefit of readers of the FSFE Community Planet, here is my irritable comment in a more prominent form.

I don’t think I appreciate either the silent treatment or the aggression typically associated with various Free Software projects. Both communicate in some way that contributions are not really welcome: that the need for such contributions isn’t genuine, perhaps, or that the contributor somehow isn’t working hard enough or isn’t good enough to have their work integrated. Never mind that the contributor will, in many cases, be doing it in their own time and possibly even to fix something that was supposed to work in the first place.

All these projects complain about taking on the maintenance burden from contributions, yet they constantly churn up their own code and make work for themselves and any contributors still hanging on for the ride. There are projects that I used to care about that I just don’t care about any more. Primarily, for me, this would be Python: a technology I still use in my own conservative way, but where the drama and performance of Python’s own development can just shake itself out to its own disastrous conclusion as far as I am concerned. I am simply beyond caring.

Too bad that all the scurrying around trying to appeal to perceived market needs while ignoring actual needs, along with a stubborn determination to ignore instructive prior art in the various areas they are trying to improve, needlessly or otherwise, all fails to appreciate the frustrating experience for many of Python’s users today. Amongst other things, a parade of increasingly incoherent packaging tools just drives users away, heaping regret on those who chose the technology in the first place. Perhaps someone’s corporate benefactor should have invested in properly addressing these challenges, but that patronage was purely opportunism, as some are sadly now discovering.

Let the core developers of these technologies do end-user support and fix up their own software for a change. If it doesn’t happen, why should I care? It isn’t my role to sustain whatever lifestyle these people feel that they’re entitled to.

Sunday, 08 June 2025

A tale of two pull requests

In November 2015, rmcgibbo opened Twine Issue #153. Less than two months later, he closed it with no explanation. The motive behind this baffling move might have remained an unsolved Internet mystery if not for one crucial fact: someone asked and rmcgibbo was willing to talk:

thedrow on Dec 31, 2015ContributorWere you able to resolve the issue?rmcgibbo on Dec 31, 2015AuthorNo. I decided I don’t care.

We all had such moments, and this humorous exchange serves as a reminder that certain matters are not worth stressing about. Like Marcus Aurelius once said, ‘choose not to be harmed — and you won’t feel harmed.’ However, instead of discussing philosophy, I want to bring up some of my experiences to make a point about contributions to free software projects.

The two pull requests

Rather than London and Paris, this tale takes place on GitHub and linux-kernel mailing list. The two titular pull requests (PRs) are of my own making and contrast between them help discuss and critique Rust’s development process.

Matching OS strings in Rust

At the beginning of 2023, I started looking into adding features to Rust that would allow for basic parsing of OsStr values.1 I eventually stumbled upon RFC 1309 and RFC 2295 which described exactly what I needed. The only problem was that they lacked an implementation. I set out to change that.

I submitted the OsStr pattern matching PR inspired by those RFCs in March 2023. Throughout April and May, I made various minor fixes to address Windows test failures, all while waiting for a reaction from the Rust project. I had no idea whether my approach was acceptable and I didn’t want to spend more time on a PR only for it to be rejected.

And waited I did. Nearly two years, until January 2025, when the Rust project finally responded. The code was accepted. A pity that I didn’t care any longer. I certainly didn’t care enough to resolve the numerous merge conflicts that had accumulated in the interim.

The PR was closed soon after and the feature remains unimplemented.

Allocating memory in Linux

In July 2010, I submitted the Contiguous Memory Allocator (CMA) to the linux-kernel. At the time, it was a relatively small patchset with only four commits. I didn’t know then that it was the beginning of quite an adventure. The code went through several revisions and required countless hours of additional work and discussions.

It was April 2012, nearly two years later, when version 24 of the patchset was eventually merged. By then, it had grown to 16 commits and included two other contributors.

On paper, both contributions took nearly two years from submission to conclusion. And yet, while I remain particularly fond of my CMA work, the Rust experience is an example of why I dislike contributing to Rust. The two years in the Linux world were filled with hours of discussion, revisions and rewarding collaboration, the two years in the Rust world were defined by silence.

Discussion

The linux-kernel is often described as a hostile environment. Linus Torvalds in particular has been criticised numerous times for his colourful outbursts. I don’t recall interacting with Linus directly, but I too have received dressing-downs; I remember the late David Brownell rightfully scolding me for my handling of USB product identifiers for example.

And yet, I would take that direct, if sometimes harsh, feedback over Rust’s silence every time.

From the perspective of a casual contributor, the Rust development process feels like a cabal of maintainers in clandestine meetings deciding which features are worth including and which are destined for the gutter. This is hyperbole, of course, but it’s born from experience. Patches are discussed in separate venues which don’t always include the author.

If the author receives a final rejection, is there a point in arguing? What arguments were made? Was their proposal misunderstood? Is there an alternative that could be proposed? Eventually, decided I don’t care.

Improvements

The improvements are obvious, though hardly easy: transparency and simplicity.

All substantive discussion about a PR should happen on that PR, with the author and other contributors included. A healthy free software project should not include ‘we discussed this in the libs-api meeting today, and decided X’ comments as a regular part of contribution process. It leaves the very person who did the work in the dark as to arguments that were made.

The contribution process should be simplified by reducing the bureaucracy. When are Request for Comment (RFCs) and API Change Proposals (ACP) needed exactly? What are the different GitHub labels? A casual contributor has little chance to understand that. In the handful of times my patches were merged, I still had no idea what process to follow.

RFC process in particular should die quick yet painful death. By design, it separates the discussion of a feature from its implementation. This leads to accepted RFCs that are never implemented (perhaps because the author lacked or lost the intention to carry it through) or implemented differently than originally documented (for example, when a superior approach is discovered during development). If someone has an idea worth discussing, let them send a patchset and discuss it on the PR. After all, ‘talk is cheep’.2

Rust’s perspective

Then again, I’m just one engineer with a handful of Rust contributions, and these are merely my experiences. Different projects have different needs, and the processes governing them have been established for a reason. Coordinating work on a sizable codebase is non-trivial, especially with a limited pool of largely volunteers, and necessitates some form of structure.

In large projects, it’s often infeasible to include everyone in all discussions. Linux has its version of ‘clandestine’ meetings in the form of invitation-only maintainer summits. However, their scope is much broader, and most low-level discussions on any particular feature happen in the open on the mailing list.

Similarly, the Rust project should, in my opinion, consider whether its current operational methods are limiting its pool of potential contributors. It’s easy to dismiss this post and my contributions, but that misses the point: For every person who complains, there are many who remain silent.3

Final Thoughts

This isn’t just a story about Rust. It’s a lesson for any large-scale project. The most valuable resource is not the code that gets merged, but the goodwill of the community that writes it. When contributors are made to feel that their efforts are disappearing into a void, they won’t just close their PRs; they will quietly stop carrying.

PS. To demonstrate that such problems aren’t unique to Rust, in the addendum article, I bring up an example of another of my failed contribution, this time to Python.

1 For those unfamiliar with Rust, OsStr and OsString are string types with a platform-dependent representation. They are used when interacting with the operating system. For example, program arguments are passed as OsString objects and file paths are built on top of them. Because the representation is not portable, there is no safe system-agnostic way to perform even the most basic parsing. For example, if an application is executed with -ooutput-file.webp command line option, Rust program has to use third-party libraries, platform-dependent code or unsafe code to split the argument into -o and output-file.webp parts. ↩

2 Linus. Torvalds. 2000. A message to linux-kernel mailing list.

3 John Goodman. 1999. Basic facts on customer complaint behavior and the impact of service on the bottom line. Competitive Advantage 9, 1 (June 1999), 1–5. ↩

Thursday, 05 June 2025

Mobile blogging, the past and the future

This blog has been running more or less continuously since mid-nineties. The site has existed in multiple forms, and with different ways to publish. But what’s common is that at almost all points there was a mechanism to publish while on the move.

Psion, documents over FTP

In the early 2000s we were into adventure motorcycling. To be able to share our adventures, we implemented a way to publish blogs while on the go. The device that enabled this was the Psion Series 5, a handheld computer that was very much a device ahead of its time.

The Psion had a reasonably sized keyboard and a good native word processing app. And battery life good for weeks of usage. Writing while underway was easy. The Psion could use a mobile phone as a modem over an infrared connection, and with that we could upload the documents to a server over FTP.

Server-side, a cron job would grab the new documents, converting them to HTML and adding them to our CMS.

In the early days of GPRS, getting this to work while roaming was quite tricky. But the system served us well for years.

If we wanted to include photos to the stories, we’d have to find an Internet cafe.

- To the Alps is a post from these times. Lots more in the motorcycling category

SMS and MMS

For an even more mobile setup, I implemented an SMS-based blogging system. We had an old phone connected to a computer back in the office, and I could write to my blog by simply sending a text. These would automatically end up as a new paragraph in the latest post. If I started the text with NEWPOST, an empty blog post would be created with the rest of that message’s text as the title.

- In the Caucasus is a good example of a post from this era

As I got into neogeography, I could also send a NEWPOSITION message. This would update my position on the map, connecting weather metadata to the posts.

As camera phones became available, we wanted to do pictures too. For the Death Monkey rally where we rode minimotorcycles from Helsinki to Gibraltar, we implemented an MMS-based system. With that the entries could include both text and pictures. But for that you needed a gateway, which was really only realistic for an event with sponsors.

- Mystery of the Missing Monkey is typical. Some more in Internet Archive

Photos over email

A much easier setup than MMS was to slightly come back to the old Psion setup, but instead of word documents, sending email with picture attachments. This was something that the new breed of (pre-iPhone) smartphones were capable of. And by now the roaming question was mostly sorted.

And so my blog included a new “moblog” section. This is where I could share my daily activities as poor-quality pictures. Sort of how people would use Instagram a few years later.

- Internet Archive has some of my old moblogs but nowadays, I post similar stuff on Pixelfed

Pause

Then there was sort of a long pause in mobile blogging advancements. Modern smartphones, data roaming, and WiFi hotspots had become ubiquitous.

In the meanwhile the blog also got migrated to a Jekyll-based system hosted on AWS. That means the old Midgard-based integrations were off the table.

And I traveled off-the-grid rarely enough that it didn’t make sense to develop a system.

But now that we’re sailing offshore, that has changed. Time for new systems and new ideas. Or maybe just a rehash of the old ones?

Starlink, Internet from Outer Space

Most cruising boats - ours included - now run the Starlink satellite broadband system. This enables full Internet, even in the middle of an ocean, even video calls! With this, we can use normal blogging tools. The usual one for us is GitJournal, which makes it easy to write Jekyll-style Markdown posts and push them to GitHub.

However, Starlink is a complicated, energy-hungry, and fragile system on an offshore boat. The policies might change at any time preventing our way of using it, and also the dishy itself, or the way we power it may fail.

But despite what you’d think, even on a nerdy boat like ours, loss of Internet connectivity is not an emergency. And this is where the old-style mobile blogging mechanisms come handy.

- Any of the 2025 Atlantic crossing posts is a good example of this setup in action

Inreach, texting with the cloud

Our backup system to Starlink is the Garmin Inreach. This is a tiny battery-powered device that connects to the Iridium satellite constellation. It allows tracking as well as basic text messaging.

When we head offshore we always enable tracking on the Inreach. This allows both our blog and our friends ashore to follow our progress.

I also made a simple integration where text updates sent to Garmin MapShare get fetched and published on our blog. Right now this is just plain text-based entries, but one could easily implement a command system similar to what I had over SMS back in the day.

One benefit of the Inreach is that we can also take it with us when we go on land adventures. And it’d even enable rudimentary communications if we found ourselves in a liferaft.

- There are various InReach integration hacks that could be used for more sophisticated data transfer

Sailmail and email over HF radio

The other potential backup for Starlink failures would be to go seriously old-school. It is possible to get email access via a SSB radio and a Pactor (or Vara) modem.

Our boat is already equipped with an isolated aft stay that can be used as an antenna. And with the popularity of Starlink, many cruisers are offloading their old HF radios.

Licensing-wise this system could be used either as a marine HF radio (requiring a Long Range Certificate), or amateur radio. So that part is something I need to work on. Thankfully post-COVID, radio amateur license exams can be done online.

With this setup we could send and receive text-based email. The Airmail application used for this can even do some automatic templating for position reports. We’d then need a mailbox that can receive these mails, and some automation to fetch and publish.

- Sailmail and No Foreign Land support structured data via email to update position. Their formats could be useful inspiration

Monday, 19 May 2025

Send your talks to Akademy 2025! (Now really for real)

We have moved the deadline for talk submission for Akademy 2025 to the end of the month. Submit your talks now!

https://mail.kde.org/pipermail/kde-community/2025q2/008217.html

Thursday, 15 May 2025

Consumerists Never Really Learn

Via an article about a Free Software initiative hoping to capitalise on the discontinuation of Microsoft Windows 10, I saw that the consumerists at Which? had published their own advice. Predictably, it mostly emphasises workarounds that merely perpetuate the kind of bad choices Which? has promoted over the years along with yet more shopping opportunities.

Those workarounds involve either continuing to delegate control to the same company whose abandonment of its users is the very topic of the article, or to switch to another surveillance economy supplier who will inevitably do the same when they deem it convenient. Meanwhile, the shopping opportunities involve buying a new computer – as one would entirely expect from Which? – or upgrading your existing computer, but only “if you’re using a desktop”. I guess adding more memory to a laptop or switching to solid-state media, both things that have rejuvenated a laptop from over a decade ago that continues to happily runs Linux, is beyond comprehension at Which? headquarters.

Only eventually do they suggest Ubuntu, presumably because it is the only Linux distribution they have heard of. I personally suggest Debian. That laptop happily running Linux was running Ubuntu, since that is what it was shipped with, but then Ubuntu first broke upgrades in an unhelpful way, hawking commercial support in the update interface to the confusion of the laptop’s principal user (and, by extension, to my confusion as I attempted to troubleshoot this anomalous behaviour), and also managed to put out a minor release of Dippy Dragon, or whatever it was, that was broken and rendered the machine unbootable without appropriate boot media.

Despite this being a known issue, they left this broken image around for people to download and use instead of fixing their mess and issuing a further update. That this also happened during the lockdown years when I wasn’t able to personally go and fix the problem in person, and when the laptop was also needed for things like interacting with public health services, merely reinforced my already dim view of some of Ubuntu’s release practices. Fortunately, some Debian installation media rescued the situation, and a switch to Debian was the natural outcome. It isn’t as if Ubuntu actually has any real benefits over Debian any more, anyway. If anything, the dubious custodianship of Ubuntu has made Debian the more sensible choice.

As for Which? and their advice, had the organisation actually used its special powers to shake up the corrupt computing industry, instead of offering little more than consumerist hints and tips, all the while neglecting the fundamental issues of trust, control, information systems architecture, sustainability and the kind of fair competition that the organisation is supposed to promote, then their readers wouldn’t be facing down an October deadline to fix a computer that Which? probably recommended in the first place, loaded up with anti-virus nonsense and other workarounds for the ecosystem they have lazily promoted over the years.

And maybe the British technology sector would be more than just the odd “local computer repair shop” scratching a living at one end of the scale, a bunch of revenue collectors for the US technology industry pulling down fat public sector contracts and soaking up unlimited amounts of taxpayer money at the other, and relatively little to mention in between. But that would entail more than casual shopping advice and fist-shaking at the consequences of a consumerist culture that the organisation did little to moderate, at least while it could consider itself both watchdog and top dog.

Wednesday, 07 May 2025

Qt World Summit 2025

These past two days I attended the Qt World Summit 2025

It happened in Munich in the SHOWPALAST MÃœNCHEN. The venue is HUGE, we had around 800 attendees (unofficial sources, don't trust the number too much) and it felt it could hold more. One slightly unfortunate thing is that it was a bit cold (temperatures in Munich these two days were well below the average for May) and quite some parts of the venue are outdoors, but you can't control the weather, so not much to "fix" here.

The venue is somewhat strangely focused on horses, but that's nothing more than an interesting quirk.

Qt World Summit is an event for the Qt developers around the world and the talks range from showcases of Qt in different products, to technical talks about how to improve performance along others less Qt centric talks about how to collaborate with other developers or about "modern C++".

As KDE we participated in the event with a stand trying to explain people what we do (David Redondo and Nicolas Fella were more in the stand than me, kudos to them)

For following years we may need to re-think a bit better our story for this event since I feel that "we do a Linux desktop and Free Software applications using Qt" is not really what Qt developers really care about, we maybe should focus more on "You can learn Qt in KDE, join us!" and "We have lots Free [Software] Qt libraries you can use!".