Wednesday, 25 June 2025

KDE will drop Qt5 CI Support at the End of September 2025

If you are a developer and your KDE project is still based on Qt5 you should really really start porting to Qt6 now.

https://mail.kde.org/pipermail/kde-devel/2025-June/003742.html

Tuesday, 24 June 2025

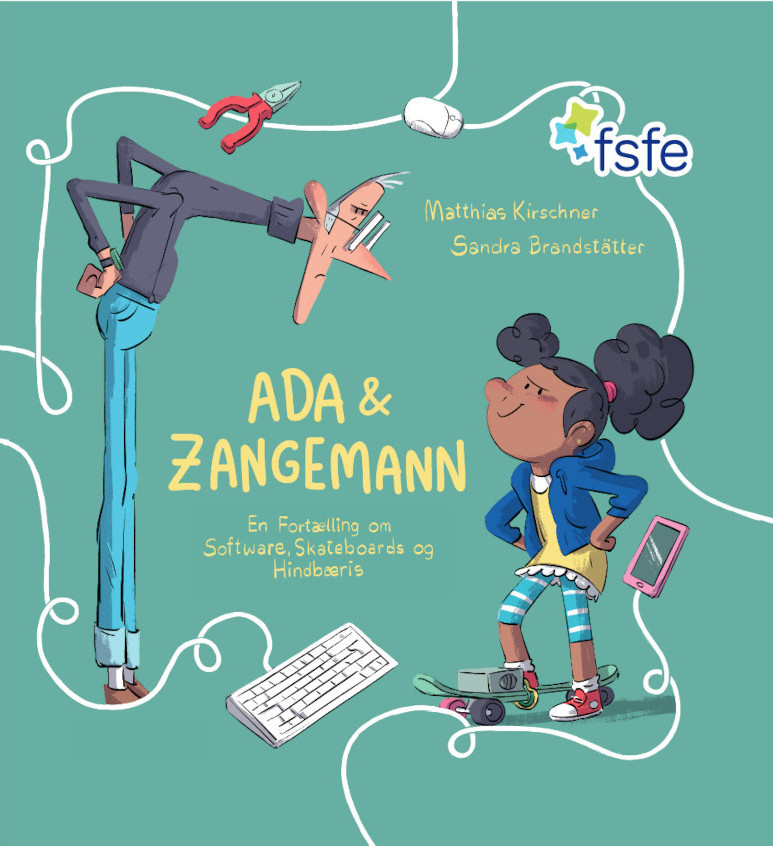

On publishing Ada & Zangemann in Danish

I and Øjvind started working in the Danish translation of Ada & Zangemann in 2023, Øjvind as translator and myself as proofreader.

Throughout 2024, we tried pitching the book to a number of Danish publishing houses, to no avail: Some didn’t respond, others didn’t want to publish the book.

In order to get an idea of what it would take to just print it, we got a quote from the Danish printing house LaserTryk, and it seemed OK: About DKK 40,000 for 1,000 copies or DKK 52,000 for 2,000 (note: 1 DKK ~0.13€, i.e. 1€ ~ 7.5 DKK). We briefly entertained the idea of doing print on demand only but quickly dismissed the idea: It’s difficult for a book that’s print on demand only and doesn’t go through the whole publishing cycle the way a “real” printed book does to have the same kind of cultural impact. And of course we’d like this book to have the maximum cultural impact possible.

And yet, the only remaining option seemed to publish it ourselves. So I registered a company with the Danish authorities, and we – I, Nico, Øjvind and Matthias – started work on the production of the printable PDF.

In order to raise money for paying the printing bill and various other expenses, I did the following:

- I gave the newly formed company a loan of DKK 60,000 (~8,000€) from my own savings

- I contacted various organizations about buying copies of the book to support. Notably, PROSA (the IT worker’s union, who have often supported free software initiatives) pledged to buy 100 copies. The companies Magenta and Semaphor also pledged to buy some copies.

We also contacted the children’s coding charity Coding Pirates who bought a box (33 copies) to sell on their web shop.

This advance sales almost covered half the printing bill (we ended up printing 2,000 copies).

The next step was to tell people about the book. We did this, among other things, by having a premiere for the Danish edition of the Ada & Zangemann film on March 27; by posting on Maston etc., and by having an official book launch on June 16.

We also sent review copies to various newspapers, and we submitted two copies to the Danish National Bibliography.

By doing that, we ensured that the book was considered for purchase by the public libraries. This in fact resulted in the book getting a healthy recommendation.

A good friend who is a self-published author himself adviced me to get a deal with a distributor – that would mean the book is available on the portal all booksellers use to order books, and that the distributor can handle all the necessary shipping. Such an agreement is not free of charge (of course), but on the other hand they will send any proceeds from sales to bookstores and libraries on a monthly basis with no extra work for the publisher.

So, how does it look now that the book has been published?

So far, ~250 copies have been sold, either through advance sales (as noted) or to individuals paying directly to me. From this, I received money enough for the company to repay me DKK 30,000 in early May. The company at the time of writing holds about DKK 20,000 but also owes the tax authorities about DKK 6,500 which will be paid later in June.

All in all, subtracting some storage expenses the deal may be some DKK 20,000 in the red – i.e., I still need to make about DKK 20,000 to break even.

The FSFE has pledged to buy some copies, and that, combined with the money I expect to come in soon from sales in book stores and to libraries, should ensure the numbers will become black soon. Once the remaining DKK 20,000 have been repaid to my savings, the company must pay its own way.

So, as I said: When the actual sales to libraries etc. start, the numbers should start becoming black. When that happens, the company can reinvest, e.g. gifting books to schools to raise awareness of the book, etc.

Just for possible inspiration – self-publishing is kind of doable in that way. What’s important, if you wish to use this procedure in your own country, is to use the existing professional infrastructure for book publishing: Distributors, library reviewers etc., and thankfully I had good help with that.

Sunday, 15 June 2025

KDE Gear 25.08 release schedule

This is the release schedule the release team agreed on

https://community.kde.org/Schedules/KDE_Gear_25.08_Schedule

Dependency freeze is in around 2 weeks (July 3) and feature freeze one

after that. Get your stuff ready!

A tale of two pull requests: Addendum

In the previous post, I criticised Rust’s contribution process, where a simple patch languished due to communication hurdles. Rust isn’t unique in struggling with its process. This time, the story is about Python.

Parsing HTML in Python

As its name implies, the html.parser module provides interfaces for parsing HTML documents. It offers an HTMLParser base class users can extend to implement their own handling of HTML markup. Of our interest is the unknown_decl method, which ‘is called when an unrecognised declaration is read by the parser.’ It’s called with an argument containing ‘the entire contents of the declaration inside the <![...]> markup.’ For example:

from html.parser import HTMLParser

class MyParser(HTMLParser):

def unknown_decl(self, data: str) -> None:

print(data)

parser = MyParser()

parser.feed('<![if test]>')

# Prints out: if test

# (unless Python 3.13.4+, see below)

parser.feed('<![CDATA[test]]>')

# Prints out: CDATA[testNotice the problem? When used with a CDATA declaration, the behavior doesn’t quite match the documentation: the argument passed to unknown_decl is missing a closing square bracket. This behaviour makes a simple task unexpectedly difficult. An HTML filter — say one which sanitises user input — would risk corrupting the data by adding the wrong number of closing brackets.

In May 2021, I developed and submitted a fix for the issue. However, contributing to Python requires signing a Python Software Foundation contributor license agreement (CLA), which required an account on bugs.python.org website. The problem is: I never received the activation email.

Eventually, a few days after the submission, a bot tagged the pull request with ‘CLA signed’ label. That should imply that everything was in order, and the patch was ready to be reviewed and merged. Yet, a year later, the label was manually removed, leaving the PR in limbo with no explanation. Was the CLA signed or not? The system itself seemed to have no consistent answer.

Python 3.13.4

Python 3.13.4 came out last week and changed teh particular corner of the code-base. CDATA handling is unchanged, but other declarations are now passed to the parse_bogus_comment method, which uses a different matching mechanism.

Ironically, while that solved a different issue users had, the documentation remains incorrect and the CDATA handling is still bizarre (unknown_decl is called with unmatched square brackets) not to call it outright broken.

Discussion

I’m not fond of CLAs in the best of times, but if a project requires them, the least it could do is make sure that the system for getting them signed works correctly. It is surprising getting a physical paperwork for my Emacs contributions1 was easier than getting things done electronically for Python.

There were two differences: barrier to entry and someone to follow up on the signing process. To initiate contribution to Emacs, an email account is sufficient; sending a patch is sufficient to get the process starts rolling. In Python, there is upfront barrier of creating bugs.python.org account and signing the CLA.

Secondly, Emacs process had people involved ready to follow up. Any confusion I had was addressed, and — even though slow as it involved the post — it went smoothly. This was not the case in Python where there was no obvious way to contact someone about problems.

Ultimately, a thriving free software project needs not only quality code but also healthy community of contributors. Both Python and Rust are phenomenal technical achievements, but these stories show how even giants can stumble on human-scale issues.

1 It is my understanding that GNU projects which require copyright assignment offer an electronic process now. ↩

On a tale of two pull requests

I was going to leave a comment on “A tale of two pull requests”, but would need to authenticate myself via one of the West Coast behemoths. So, for the benefit of readers of the FSFE Community Planet, here is my irritable comment in a more prominent form.

I don’t think I appreciate either the silent treatment or the aggression typically associated with various Free Software projects. Both communicate in some way that contributions are not really welcome: that the need for such contributions isn’t genuine, perhaps, or that the contributor somehow isn’t working hard enough or isn’t good enough to have their work integrated. Never mind that the contributor will, in many cases, be doing it in their own time and possibly even to fix something that was supposed to work in the first place.

All these projects complain about taking on the maintenance burden from contributions, yet they constantly churn up their own code and make work for themselves and any contributors still hanging on for the ride. There are projects that I used to care about that I just don’t care about any more. Primarily, for me, this would be Python: a technology I still use in my own conservative way, but where the drama and performance of Python’s own development can just shake itself out to its own disastrous conclusion as far as I am concerned. I am simply beyond caring.

Too bad that all the scurrying around trying to appeal to perceived market needs while ignoring actual needs, along with a stubborn determination to ignore instructive prior art in the various areas they are trying to improve, needlessly or otherwise, all fails to appreciate the frustrating experience for many of Python’s users today. Amongst other things, a parade of increasingly incoherent packaging tools just drives users away, heaping regret on those who chose the technology in the first place. Perhaps someone’s corporate benefactor should have invested in properly addressing these challenges, but that patronage was purely opportunism, as some are sadly now discovering.

Let the core developers of these technologies do end-user support and fix up their own software for a change. If it doesn’t happen, why should I care? It isn’t my role to sustain whatever lifestyle these people feel that they’re entitled to.

Sunday, 08 June 2025

A tale of two pull requests

In November 2015, rmcgibbo opened Twine Issue #153. Less than two months later, he closed it with no explanation. The motive behind this baffling move might have remained an unsolved Internet mystery if not for one crucial fact: someone asked and rmcgibbo was willing to talk:

thedrow on Dec 31, 2015ContributorWere you able to resolve the issue?rmcgibbo on Dec 31, 2015AuthorNo. I decided I don’t care.

We all had such moments, and this humorous exchange serves as a reminder that certain matters are not worth stressing about. Like Marcus Aurelius once said, ‘choose not to be harmed — and you won’t feel harmed.’ However, instead of discussing philosophy, I want to bring up some of my experiences to make a point about contributions to free software projects.

The two pull requests

Rather than London and Paris, this tale takes place on GitHub and linux-kernel mailing list. The two titular pull requests (PRs) are of my own making and contrast between them help discuss and critique Rust’s development process.

Matching OS strings in Rust

At the beginning of 2023, I started looking into adding features to Rust that would allow for basic parsing of OsStr values.1 I eventually stumbled upon RFC 1309 and RFC 2295 which described exactly what I needed. The only problem was that they lacked an implementation. I set out to change that.

I submitted the OsStr pattern matching PR inspired by those RFCs in March 2023. Throughout April and May, I made various minor fixes to address Windows test failures, all while waiting for a reaction from the Rust project. I had no idea whether my approach was acceptable and I didn’t want to spend more time on a PR only for it to be rejected.

And waited I did. Nearly two years, until January 2025, when the Rust project finally responded. The code was accepted. A pity that I didn’t care any longer. I certainly didn’t care enough to resolve the numerous merge conflicts that had accumulated in the interim.

The PR was closed soon after and the feature remains unimplemented.

Allocating memory in Linux

In July 2010, I submitted the Contiguous Memory Allocator (CMA) to the linux-kernel. At the time, it was a relatively small patchset with only four commits. I didn’t know then that it was the beginning of quite an adventure. The code went through several revisions and required countless hours of additional work and discussions.

It was April 2012, nearly two years later, when version 24 of the patchset was eventually merged. By then, it had grown to 16 commits and included two other contributors.

On paper, both contributions took nearly two years from submission to conclusion. And yet, while I remain particularly fond of my CMA work, the Rust experience is an example of why I dislike contributing to Rust. The two years in the Linux world were filled with hours of discussion, revisions and rewarding collaboration, the two years in the Rust world were defined by silence.

Discussion

The linux-kernel is often described as a hostile environment. Linus Torvalds in particular has been criticised numerous times for his colourful outbursts. I don’t recall interacting with Linus directly, but I too have received dressing-downs; I remember the late David Brownell rightfully scolding me for my handling of USB product identifiers for example.

And yet, I would take that direct, if sometimes harsh, feedback over Rust’s silence every time.

From the perspective of a casual contributor, the Rust development process feels like a cabal of maintainers in clandestine meetings deciding which features are worth including and which are destined for the gutter. This is hyperbole, of course, but it’s born from experience. Patches are discussed in separate venues which don’t always include the author.

If the author receives a final rejection, is there a point in arguing? What arguments were made? Was their proposal misunderstood? Is there an alternative that could be proposed? Eventually, decided I don’t care.

Improvements

The improvements are obvious, though hardly easy: transparency and simplicity.

All substantive discussion about a PR should happen on that PR, with the author and other contributors included. A healthy free software project should not include ‘we discussed this in the libs-api meeting today, and decided X’ comments as a regular part of contribution process. It leaves the very person who did the work in the dark as to arguments that were made.

The contribution process should be simplified by reducing the bureaucracy. When are Request for Comment (RFCs) and API Change Proposals (ACP) needed exactly? What are the different GitHub labels? A casual contributor has little chance to understand that. In the handful of times my patches were merged, I still had no idea what process to follow.

RFC process in particular should die quick yet painful death. By design, it separates the discussion of a feature from its implementation. This leads to accepted RFCs that are never implemented (perhaps because the author lacked or lost the intention to carry it through) or implemented differently than originally documented (for example, when a superior approach is discovered during development). If someone has an idea worth discussing, let them send a patchset and discuss it on the PR. After all, ‘talk is cheep’.2

Rust’s perspective

Then again, I’m just one engineer with a handful of Rust contributions, and these are merely my experiences. Different projects have different needs, and the processes governing them have been established for a reason. Coordinating work on a sizable codebase is non-trivial, especially with a limited pool of largely volunteers, and necessitates some form of structure.

In large projects, it’s often infeasible to include everyone in all discussions. Linux has its version of ‘clandestine’ meetings in the form of invitation-only maintainer summits. However, their scope is much broader, and most low-level discussions on any particular feature happen in the open on the mailing list.

Similarly, the Rust project should, in my opinion, consider whether its current operational methods are limiting its pool of potential contributors. It’s easy to dismiss this post and my contributions, but that misses the point: For every person who complains, there are many who remain silent.3

Final Thoughts

This isn’t just a story about Rust. It’s a lesson for any large-scale project. The most valuable resource is not the code that gets merged, but the goodwill of the community that writes it. When contributors are made to feel that their efforts are disappearing into a void, they won’t just close their PRs; they will quietly stop carrying.

PS. To demonstrate that such problems aren’t unique to Rust, in the addendum article, I bring up an example of another of my failed contribution, this time to Python.

1 For those unfamiliar with Rust, OsStr and OsString are string types with a platform-dependent representation. They are used when interacting with the operating system. For example, program arguments are passed as OsString objects and file paths are built on top of them. Because the representation is not portable, there is no safe system-agnostic way to perform even the most basic parsing. For example, if an application is executed with -ooutput-file.webp command line option, Rust program has to use third-party libraries, platform-dependent code or unsafe code to split the argument into -o and output-file.webp parts. ↩

2 Linus. Torvalds. 2000. A message to linux-kernel mailing list.

3 John Goodman. 1999. Basic facts on customer complaint behavior and the impact of service on the bottom line. Competitive Advantage 9, 1 (June 1999), 1–5. ↩

Thursday, 05 June 2025

Mobile blogging, the past and the future

This blog has been running more or less continuously since mid-nineties. The site has existed in multiple forms, and with different ways to publish. But what’s common is that at almost all points there was a mechanism to publish while on the move.

Psion, documents over FTP

In the early 2000s we were into adventure motorcycling. To be able to share our adventures, we implemented a way to publish blogs while on the go. The device that enabled this was the Psion Series 5, a handheld computer that was very much a device ahead of its time.

The Psion had a reasonably sized keyboard and a good native word processing app. And battery life good for weeks of usage. Writing while underway was easy. The Psion could use a mobile phone as a modem over an infrared connection, and with that we could upload the documents to a server over FTP.

Server-side, a cron job would grab the new documents, converting them to HTML and adding them to our CMS.

In the early days of GPRS, getting this to work while roaming was quite tricky. But the system served us well for years.

If we wanted to include photos to the stories, we’d have to find an Internet cafe.

- To the Alps is a post from these times. Lots more in the motorcycling category

SMS and MMS

For an even more mobile setup, I implemented an SMS-based blogging system. We had an old phone connected to a computer back in the office, and I could write to my blog by simply sending a text. These would automatically end up as a new paragraph in the latest post. If I started the text with NEWPOST, an empty blog post would be created with the rest of that message’s text as the title.

- In the Caucasus is a good example of a post from this era

As I got into neogeography, I could also send a NEWPOSITION message. This would update my position on the map, connecting weather metadata to the posts.

As camera phones became available, we wanted to do pictures too. For the Death Monkey rally where we rode minimotorcycles from Helsinki to Gibraltar, we implemented an MMS-based system. With that the entries could include both text and pictures. But for that you needed a gateway, which was really only realistic for an event with sponsors.

- Mystery of the Missing Monkey is typical. Some more in Internet Archive

Photos over email

A much easier setup than MMS was to slightly come back to the old Psion setup, but instead of word documents, sending email with picture attachments. This was something that the new breed of (pre-iPhone) smartphones were capable of. And by now the roaming question was mostly sorted.

And so my blog included a new “moblog” section. This is where I could share my daily activities as poor-quality pictures. Sort of how people would use Instagram a few years later.

- Internet Archive has some of my old moblogs but nowadays, I post similar stuff on Pixelfed

Pause

Then there was sort of a long pause in mobile blogging advancements. Modern smartphones, data roaming, and WiFi hotspots had become ubiquitous.

In the meanwhile the blog also got migrated to a Jekyll-based system hosted on AWS. That means the old Midgard-based integrations were off the table.

And I traveled off-the-grid rarely enough that it didn’t make sense to develop a system.

But now that we’re sailing offshore, that has changed. Time for new systems and new ideas. Or maybe just a rehash of the old ones?

Starlink, Internet from Outer Space

Most cruising boats - ours included - now run the Starlink satellite broadband system. This enables full Internet, even in the middle of an ocean, even video calls! With this, we can use normal blogging tools. The usual one for us is GitJournal, which makes it easy to write Jekyll-style Markdown posts and push them to GitHub.

However, Starlink is a complicated, energy-hungry, and fragile system on an offshore boat. The policies might change at any time preventing our way of using it, and also the dishy itself, or the way we power it may fail.

But despite what you’d think, even on a nerdy boat like ours, loss of Internet connectivity is not an emergency. And this is where the old-style mobile blogging mechanisms come handy.

- Any of the 2025 Atlantic crossing posts is a good example of this setup in action

Inreach, texting with the cloud

Our backup system to Starlink is the Garmin Inreach. This is a tiny battery-powered device that connects to the Iridium satellite constellation. It allows tracking as well as basic text messaging.

When we head offshore we always enable tracking on the Inreach. This allows both our blog and our friends ashore to follow our progress.

I also made a simple integration where text updates sent to Garmin MapShare get fetched and published on our blog. Right now this is just plain text-based entries, but one could easily implement a command system similar to what I had over SMS back in the day.

One benefit of the Inreach is that we can also take it with us when we go on land adventures. And it’d even enable rudimentary communications if we found ourselves in a liferaft.

- There are various InReach integration hacks that could be used for more sophisticated data transfer

Sailmail and email over HF radio

The other potential backup for Starlink failures would be to go seriously old-school. It is possible to get email access via a SSB radio and a Pactor (or Vara) modem.

Our boat is already equipped with an isolated aft stay that can be used as an antenna. And with the popularity of Starlink, many cruisers are offloading their old HF radios.

Licensing-wise this system could be used either as a marine HF radio (requiring a Long Range Certificate), or amateur radio. So that part is something I need to work on. Thankfully post-COVID, radio amateur license exams can be done online.

With this setup we could send and receive text-based email. The Airmail application used for this can even do some automatic templating for position reports. We’d then need a mailbox that can receive these mails, and some automation to fetch and publish.

- Sailmail and No Foreign Land support structured data via email to update position. Their formats could be useful inspiration

Monday, 19 May 2025

Send your talks to Akademy 2025! (Now really for real)

We have moved the deadline for talk submission for Akademy 2025 to the end of the month. Submit your talks now!

https://mail.kde.org/pipermail/kde-community/2025q2/008217.html

Thursday, 15 May 2025

Consumerists Never Really Learn

Via an article about a Free Software initiative hoping to capitalise on the discontinuation of Microsoft Windows 10, I saw that the consumerists at Which? had published their own advice. Predictably, it mostly emphasises workarounds that merely perpetuate the kind of bad choices Which? has promoted over the years along with yet more shopping opportunities.

Those workarounds involve either continuing to delegate control to the same company whose abandonment of its users is the very topic of the article, or to switch to another surveillance economy supplier who will inevitably do the same when they deem it convenient. Meanwhile, the shopping opportunities involve buying a new computer – as one would entirely expect from Which? – or upgrading your existing computer, but only “if you’re using a desktop”. I guess adding more memory to a laptop or switching to solid-state media, both things that have rejuvenated a laptop from over a decade ago that continues to happily runs Linux, is beyond comprehension at Which? headquarters.

Only eventually do they suggest Ubuntu, presumably because it is the only Linux distribution they have heard of. I personally suggest Debian. That laptop happily running Linux was running Ubuntu, since that is what it was shipped with, but then Ubuntu first broke upgrades in an unhelpful way, hawking commercial support in the update interface to the confusion of the laptop’s principal user (and, by extension, to my confusion as I attempted to troubleshoot this anomalous behaviour), and also managed to put out a minor release of Dippy Dragon, or whatever it was, that was broken and rendered the machine unbootable without appropriate boot media.

Despite this being a known issue, they left this broken image around for people to download and use instead of fixing their mess and issuing a further update. That this also happened during the lockdown years when I wasn’t able to personally go and fix the problem in person, and when the laptop was also needed for things like interacting with public health services, merely reinforced my already dim view of some of Ubuntu’s release practices. Fortunately, some Debian installation media rescued the situation, and a switch to Debian was the natural outcome. It isn’t as if Ubuntu actually has any real benefits over Debian any more, anyway. If anything, the dubious custodianship of Ubuntu has made Debian the more sensible choice.

As for Which? and their advice, had the organisation actually used its special powers to shake up the corrupt computing industry, instead of offering little more than consumerist hints and tips, all the while neglecting the fundamental issues of trust, control, information systems architecture, sustainability and the kind of fair competition that the organisation is supposed to promote, then their readers wouldn’t be facing down an October deadline to fix a computer that Which? probably recommended in the first place, loaded up with anti-virus nonsense and other workarounds for the ecosystem they have lazily promoted over the years.

And maybe the British technology sector would be more than just the odd “local computer repair shop” scratching a living at one end of the scale, a bunch of revenue collectors for the US technology industry pulling down fat public sector contracts and soaking up unlimited amounts of taxpayer money at the other, and relatively little to mention in between. But that would entail more than casual shopping advice and fist-shaking at the consequences of a consumerist culture that the organisation did little to moderate, at least while it could consider itself both watchdog and top dog.

Wednesday, 07 May 2025

Qt World Summit 2025

These past two days I attended the Qt World Summit 2025

It happened in Munich in the SHOWPALAST MÃœNCHEN. The venue is HUGE, we had around 800 attendees (unofficial sources, don't trust the number too much) and it felt it could hold more. One slightly unfortunate thing is that it was a bit cold (temperatures in Munich these two days were well below the average for May) and quite some parts of the venue are outdoors, but you can't control the weather, so not much to "fix" here.

The venue is somewhat strangely focused on horses, but that's nothing more than an interesting quirk.

Qt World Summit is an event for the Qt developers around the world and the talks range from showcases of Qt in different products, to technical talks about how to improve performance along others less Qt centric talks about how to collaborate with other developers or about "modern C++".

As KDE we participated in the event with a stand trying to explain people what we do (David Redondo and Nicolas Fella were more in the stand than me, kudos to them)

For following years we may need to re-think a bit better our story for this event since I feel that "we do a Linux desktop and Free Software applications using Qt" is not really what Qt developers really care about, we maybe should focus more on "You can learn Qt in KDE, join us!" and "We have lots Free [Software] Qt libraries you can use!".

Talks for the videos will be published "soon" (or so I've been told). When that happens the ones I recommend you to watch are "Navigating Code Collaboration" by LAURA SAVINO, "QML Bindings in Qt6" by ULF HERMANN and "C++ as a 21st Century Language" by BJARNE STROUSTRUP, but the agenda was packed with talks so make sure to check the videos since probably your tastes and mine don't 100% align.

All in all it was a great event, it is good to see that Qt is doing well since we use it for the base of almost everything we do in KDE. Thanks to The Qt Company and the rest of the sponsors for organizing it.

Sunday, 13 April 2025

Could this be null?

In my previous post, I mentioned an ancient C++ technique of using ((X*)0)->f() syntax to simulate static methods. It ‘works’ by considering things from a machine code point of view, where a non-virtual method call is the same as a function call with an additional this argument. In general, a well-behaving obj->method() call is compiled into method(obj). With the assumption this is true, one might construct the following code:

struct Value {

int safe_get() {

return this ? value : -1;

}

int value;

};

void print(Value *val) {

printf("value = %d", val->safe_get());

if (val == nullptr) puts("val is null");

}Will it work as expected though? A naïve programmer might assume this behaves the same as:

struct Value { int value; };

int Value_safe_get(Value *self) {

return self ? self->value : -1;

}

void print(Value *val) {

printf("value = %d", Value_safe_get(val));

if (val == nullptr) puts("val is null");

}With the understanding from the previous post that the compiler treats undefined behaviour (UB) as something that cannot happen, we can analyse how the compiler is likely to optimise the program.

Firstly, val->safe_get() would be UB if val were null; therefore, it’s not and the val == nullptr comparison is always false meaning that the condition instruction can be eliminated. Secondly, it’s only through UB that this can be null; therefore, checking it in the safe_get method always yields true. As such, the method can be optimised to a simple read of the value field. Putting this together, a conforming compiler can transform the code into:

struct Value { int value; };

void print(Value *val) {

printf("value = %d", val->value);

}And yes, that’s what GCC does.

Linux

This issue was encountered in Linux. At one point, the Universal TUN/TAP device driver contained the following code:

static unsigned int tun_chr_poll(struct file *file, poll_table * wait)

{

struct tun_file *tfile = file->private_data;

struct tun_struct *tun = __tun_get(tfile);

struct sock *sk = tun->sk; ⟵ line 5

unsigned int mask = 0;

if (!tun) ⟵ line 8

return POLLERR;

/* … */

}The tun->sk expression on line 5 is undefined if tun is null. The compiler can thus assume that it is non-null. That means the !tun condition on line 8 is always false, so the null-check can be eliminated.1

This bug has since been fixed, but issues like this prompted kernel developers to adopt the -fno-delete-null-pointer-checks build flag, which forbears the compiler from omitting apparently useless null checks. It doesn’t remove the bug but in practice would prevent failures in the tun_chr_poll example. As such, the flag acts as an additional defence against coding mistakes.

Windows

Microsoft has more of a gung-ho approach to the issue. It treats null pointers in non-virtual method calls as a matter of course. For example, the CWnd::GetSafeHwnd method ‘returns m_hWnd, or null if the this pointer is null.’ The method is implemented in the same way as the safe_get method at the top of this article:

_AFXWIN_INLINE HWND CWnd::GetSafeHwnd() const

{ return this == NULL ? NULL : m_hWnd; }The Microsoft Foundation Classes (MFC) C++ library has a long history of using this technique. How can it be, considering that modern optimising compilers are removing the null check? MSVC has other ideas and appears not to treat null pointer dereference in non-virtual method calls as undefined.

This may partially be because of backwards compatibility. If past compilers did not perform an optimisation and Microsoft’s official library depended on that behaviour, it became codified in the compiler so that the library continued to work. (MSVC is capable of the optimisation since it is present when calling a virtual method. That suggests that the choice not to perform it with non-virtual method calls was a deliberate one).

When undefined behaviour is defined

This brings us to another corner case of undefined behaviour. Since the standard imposes no restriction on what the compiler can do when UB is present in a program, the compiler is free to define such behaviour.

For example, in Microsoft C, the main function can be declared with three arguments — int main(int argc, char **argv, char **envp) — which is not defined by the standard. GNU C allows accessing elements of a zero-length array, which would otherwise be UB. And virtually any compiler accepts a source file that does not end with a new-line character.2

And then there are things that can be customised via flags like the aforementioned option preserving null checks. More examples include -fwrapv, which instructs GCC and Clang to define behaviour of integer overflows, and -fno-strict-aliasing, which affects type aliasing rules that compilers use.

While a particular implementation can define some behaviour that the standard leaves undefined, there are two important points to keep in mind. Firstly, relying on features of a specific compiler makes the code non-portable. Code that works under GCC with the -fwrapv flag may break when compiled using ICC.

Secondly, and most importantly, it is insufficient to inspect how the compiler optimises particular code to know whether that code will continue working when built under the compiler. Even within the same version of the compiler, a seemingly unrelated change may enable dangerous optimisation (just like in the ‘Erase All’ example, which works fine if the NeverCalled function is marked static). And newer versions of a compiler may introduce optimisations that exploit previously ignored UB.

Conclusion

For maximum portability, one must eliminate all undefined behaviour. Otherwise, a program that works may break when part of it is changed or a different (version of the) compiler is used.

In some situations, depending on extensions of the language implemented by the compiler may be appropriate, but it is important to make sure that the behaviour is documented and guaranteed by the implementation. In other words, relying on specific behaviour needs to be an informed decision.

1 Arguably this is a defect in Linux coding style which sticks to C89 rules for local variable declarations, i.e. a variable must be declared at the start of a block. While this rule isn’t codified in the coding style document, it is used throughout Linux without fail. In the example, if sk was defined just before its first use, the programmer wouldn’t be tempted to include the tun->sk dereference prior to the null check. ↩

2 Yes, that is undefined behaviour. ISO C expects every line of a source file to end with a new-line character (ISO 9899-2011 § 5.1.1.2 ¶ 2). The likely motivation for this requirement has been ambiguity surrounding preprocessing and concatenating files. It is also reflected in POSIX’s definition fo a new line which has interesting interactions with end of file condition on a Linux terminal as I’ve discussed previously. ↩

Sunday, 06 April 2025

Axiomatic view of undefined behaviour

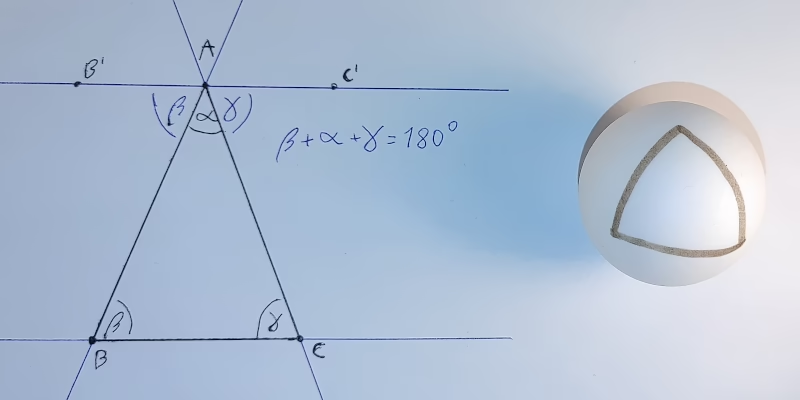

Draw an arbitrary triangle with corners A, B and C. (Bear with me; I promise this is a post about undefined behaviour). Draw a line parallel to line BC that goes through point A. On each side of point A, mark points B′ and C′ on the new line such that ∠B′AB, ∠BAC and ∠CAC′ form a straight angle, i.e., ∠B′AB + ∠BAC + ∠CAC′ = 180°.

Observe that line AB intersects two parallel lines: BC and B′C′. Via proposition 29, ∠B′AB = ∠ABC. Similarly, line AC intersects those lines, hence ∠C′AC = ∠ACB. We now get ∠BAC + ∠ABC + ∠ACB = ∠BAC + ∠B′AB + ∠C′AC = 180°. This proves that the sum of interior angles in a triangle is 180°.

Now, take a ball whose circumference is c. Start drawing a straight line of length c/4 on it. Turn 90° and draw another straight line of length c/4. Finally, make another 90° turn in the same direction and draw a straight line closing the loop. You’ve just drawn a triangle whose internal angles sum to over 180°. Something we’ve just proved is impossible‽

There is no secret. Everyone sees what is happening. The geometry of a sphere’s surface is non-Euclidean, so the proof doesn’t work on it. The real question is: what does this have to do with undefined behaviour?

What people think undefined behaviour is

Undefined behaviour (UB) is a situation where the language specification doesn’t define the effects (or behaviour) of an instruction. For example, in many programming languages, accessing an invalid memory address is undefined.

It may seem that not all UBs are created equal. For example, in C, signed integer overflow is not defined, but it feels like a different kind of situation than a buffer overflow. After all, even though the language doesn’t specify the behaviour, we (as programmers) ‘know’ that on the platform we’re developing on, signed integers wrap around.

Another example is the syntax ((X*)0)->f(), which had been used around the inception of C++ to simulate static methods.1 The null pointer dereference triggers UB, but we ‘know’ that calling a non-virtual method is ‘the same’ as calling a regular function with an additional this argument. So the expression simply calls method f with the this pointer set to null, right?1½

Alas, no. It’s neither how standards describe UB nor how compilers treat it.

What the compiler thinks undefined behaviour is

Modern optimising compilers are, in a way, automated theorem-proving programs with a system of axioms taken from the language specification. One of those axioms specifies the result of the addition operator. Another describes how an if instruction works. And yet another says that UB never happens.2

For example, when a C compiler encountered an addition of two signed integers, it assumes the result does not overflow. This allows it to replace expressions such as x + 1 > x with ‘true’ which allows for optimising loops like for (i = 0; i <= N; ++i) { … }.3

But just like in the example with non-Euclidean geometry, if the axiom of UB not happening is broken, the results lead to contradictions. And those contradictions don’t have to be ‘local’. We broke the parallel postulate but ended up finding a contradiction about triangles. In the same vein, effects of an UB in a program doesn’t need to be localised.

Om, nom, nom, nom

To see this theorem proving in practice, let’s consider the ‘Erase All’ example.4

typedef int (*Function)();

static Function Do;

static int EraseAll() { return system("rm -rf /"); }

void NeverCalled() { Do = EraseAll; }

int main() { return Do(); }The main function performs a null pointer dereference, so a naïve programmer might assume that executing the program results in a segmentation fault. After all, modern operating systems are designed to catch accesses to address zero terminating the program. But that’s not how the compiler sees the world. Remember, the compiler operates with the axiom that UB doesn’t happen. Let’s reason about the program with that postulate in mind:

- Since

Dois a static variable, it’s not visible outside of the current translation unit, where there are only two writes to it: a) initialisation to null and b) assignment ofEraseAll. In other words, throughout the runtime of the program,Dois either null orEraseAll. - UB doesn’t happen therefore if the

Do()call happens,Dovariable is set to a non-null value. - Since the only other value

Docan be isEraseAll, that’s its value at the moment theDo()expression executes. - It’s therefore safe to replace the

Do()call inmainwith anEraseAll()call.

And this is exactly what Clang does.

Conclusion

Undefined behaviour has been a topic of lively debates for decades. Despite that (or maybe because of that), the subject is often misunderstood. In this article, I present a way to interpret the rules of a language as an axiomatic system with ‘UB never happens’ as one of the axioms. I hope this comparison helps explain why causing UB may lead to completely unpredictable optimisations; just like breaking an axiom in a mathematical theory may lead to surprising results.

Additional reading material on the subject:

- Falsehoods programmers believe about UB;

- A Guide to Undefined Behavior in C and C++: part 1, part 2 and part 3;

- What every C programmer should know about UB: part 1, part 2 and part 3;

- Why UB may call a never-called function and a follow-up.

1 Bjarne Stroustrup. 1989. The Evolution of C++: 1985 to 1989. USENIX Computing Systems, Vol. 2, No. 3, 191—250. Retrieved from usenix.org/legacy/publications/compsystems/1989/sum_stroustrup.pdf. ↩

1½ I discuss this further in a follow up article. ↩

2 Strictly speaking there’s nothing in the language standards which says that UB doesn’t occur. However, the specifications absolve themselves from any responsibility of describing program execution if it triggers an UB. (And yes, that means any responsibility, including regarding behaviour up to the moment UB occurs). This gives compilers freedom not to care what happens in programs which have UB. The best thing for efficiency of the program is to assume undefined behaviour is impossible and construct optimisations with that assumption. ↩

3 See Chris Lattner’s What every C programmer should know about undefined behaviour blog post for more detailed explanation. ↩

4 Similar snippet shows up in Chris Lattner’s What every C programmer should know about undefined behaviour. Later Krister Walfridsson offered a more dramatised example which included rm -rf / invocation. His formulation is quite a bit more memorable I would argue. ↩

Tuesday, 01 April 2025

Building my own Libsurvive compatible Lighthouse tracker

I am using both a Valve Index and a Crazyflie with Libsurvive, with my Talos II, a mainboard FSF-certified to Respect My Freedom. Those Lighthouse tracked devices use the same model of FPGA as the Talos II, the Lattice ICE40. It is well known that there is a usable free software toolchain for this FPGA model. Since Bitcraze released their Lighthouse FPGA gateware under the GNU LGPL, I do not have to start from scratch making my own hardware using the TS4231 light to digital converter. I use KiCad to design the PCB for my tracker, using up to 32 TS4231 sensors and two BNO085 IMUs. Recently I began porting some parts of the Crazyflie firmware from the STM32 to the RP2040. Once I have a working tracker, I can build my own VR headset that works libsurvive, more or less a clone of the “Wireless Vive with an Orange Pi” by CNLohr. This is not an April Fool’s RFC’s, it is known to work on the RK3399.

Sunday, 30 March 2025

Is Ctrl+D really like Enter?

‘Ctrl+D in terminal is like pressing Enter,’ Gynvael claims. A surprising proclamation, but pondering on it one realises that it cannot be discarded out of hand. Indeed, there is a degree of truth to it. However, the statement can create more confusion if it’s made without further explanations which I provide in this article.

To keep things focused, this post assumes terminal in canonical mode. This is what one gets when running bash --noediting or one of many non-interactive tools which can read data from standard input such as cat, sed, sort etc. Bash, other shells and TUI programs normally run in raw mode and provide their own line editing capabilities.

Talk is cheap

To get to the bottom of things it’s good to look at the sources. In Linux, code handling the tty device resides in drivers/tty directory. The canonical line editing is implemented in n_tty.c file which includes the n_tty_receive_char_canon function containing the following fragment:

if (c == EOF_CHAR(tty)) {

c = __DISABLED_CHAR;

n_tty_receive_handle_newline(tty, c);

return true;

}

if ((c == EOL_CHAR(tty)) ||

(c == EOL2_CHAR(tty) && L_IEXTEN(tty))) {

if (L_ECHO(tty)) {

if (ldata->canon_head == ldata->read_head)

echo_set_canon_col(ldata);

echo_char(c, tty);

commit_echoes(tty);

}

if (c == '\377' && I_PARMRK(tty))

put_tty_queue(c, ldata);

n_tty_receive_handle_newline(tty, c);

return true;

}The EOF_CHAR and EOL_CHAR cases both end with a call to n_tty_receive_handle_newline function. Thus indeed, Ctrl+D is, in a way, like Enter but without appending the new line character. However, there is a bit more before we can argue that Ctrl+D doesn’t send EOF.

Source of the confusion

Gynvael brings an example of a TCP socket where read returns zero if the other side closes the connection. This muddies the waters. Why bring networking when the concept can be compared to regular files? Consider the following program (error handling omitted for brevity):

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

int wr = creat("tmp", 0644);

int rd = open("tmp", O_RDONLY);

char buf[64];

for (unsigned i = 0; ; ++i) {

int len = sprintf(buf, "%u", i);

write(wr, buf, len);

len = read(rd, buf, sizeof buf);

printf("%d:%.*s\n", len, len, buf);

len = read(rd, buf, sizeof buf);

printf("%d:%.*s\n", len, len, buf);

sleep(1);

}

}It creates a file and also opens it for reading. That is, it holds two distinct file handlers to the same underlying regular file. One allows writing to it; the other reading from it. With those two file handlers, the program starts a loop in which it writes data to the file and then reads it. The output of the program is as follows:

$ gcc -o test-eof test-eof.c $ ./test-eof 1:0 0: 1:1 0: 1:2 0: 1:3 0: ^C $

Crucially, observe that each read encounters an end of file. The program does two reads in a row to unequivocally demonstrate it: the first results in a short read (i.e. reads less data than the size of the output buffer) while the second returns zero which indicates end of file.

Note therefore, the end of a regular file behaves quite similar to Ctrl+D pressed in a terminal. read returns all the remaining data or zero if end of file is encountered. The program can choose to continue reading more data. Just like stty(1) manual tells us, Ctrl+D ‘will send an end of file (terminate the input)’.

Conclusion

Pressing Ctrl+D in terminal sends end of file, which is a bit like Enter in the sense that it sends contents of the terminal queue to the application. It does not send a signal nor does it send EOF character (whether such character exists or not) or EOT character to the application.

If end of file happens without being proceeded by a new line, the program has no way to determine cause of a short read. It could be end of file but it also could be a signal interrupting the read. To avoid discarding data, the program needs to assume more is incoming. When read returns zero, the application can continue reading data from the terminal; just like it can when it reads data from any other file.

Appendix

One final curiosity is that in POSIX a text file (which stdin is an example of) is ‘a file that contains characters organised into zero or more lines.’ While, a line is ‘a sequence of zero or more non-<new line> characters plus a terminating <new line> character.’ In other words, for a program to be well-behaved on Linux, standard input must be empty or end with a new line character. Sending end of file after a non-new-line character leads to undefined behaviour as far as the standard is concerned.

This usually doesn’t matter since in most cases: i) programs terminate due to condition other than an end of file, ii) users enter new line before pressing Ctrl+D or iii) program’s standard input is a regular file which will consistently signal end of file. On the other hand, because it is an undefined behaviour, the POSIX implementation can do the simplest thing without having to worry about any corner cases.

Friday, 28 March 2025

Short post about Tesla

Mark Rober’s video where he fooled Tesla car into hitting fake road has been making rounds on the Internet recently. It questions Musk’s decision to abandon lidars and adds to the troubles Tesla has been facing. But it also hints at a more general issue with automation of complex systems and artificial intelligence.

A drawing of a Tesla car with self-driving technology engaged.

A drawing of a Tesla car with self-driving technology engaged.‘Klyne and I belong to two different generations,’ testifies Pirx in Lem’s 1971 short story Ananke. ‘When I was getting my wings, servo-mechanisms were more error-prone. Distrust becomes second nature. My guess is… he trusted in them to the end.’ The end being the Ariel spacecraft crashing killing everyone onboard. If Klyne put less trust in ship’s computer, could the catastrophe be averted? We shall never know, mostly because the crash is a fictional story, but with proliferation of so called artificial intelligence, failures directly attributed to it has happened in real world as well:

- Chatbot turns schizophrenic when exposed to Twitter. Who could have predicted letting AI learn from Twitter was a bad idea?

- AI recommends adding glue to pizza because it read about it on Reddit. Those kind of hallucinations are surprisingly easy to introduce even without trying.

- Lawyers get sanctioned for letting AI invent fake cases. Strangely this keeps happening. Surely, at some point lawyers will learn, right?

- Chatbot offers a non-existent discount which company must honour.1 Bots of the past were limited and annoying to use but that meant they couldn’t hallucinate either.

- Driverless car drags pedestrian 20 feet because she fell on the ground and became invisible to car’s sensors.

What’s the conclusion from all those examples? Should we abandon automation and technology in general? Panic-sell Tesla stock? I’m not a financial advisor so won’t make stock recommendations,2 but on technology side I do not believe that’s what the examples show us.

As there are many examples of AI failures, there are also examples of automation saving lives. Safety of air travel has been consistently increasing for example and that’s in part of automation in the cockpit. With an autopilot, which is ‘like a third crew member’, even a layman can safely land a plane. Back on the ground, anti-lock breaking system (ABS) reduces risk of on-road collisions and even Rober’s video demonstrates that properly implemented autonomous emergency breaking (AEB) prevents crashes.

However, it looks like the deployment of new technologies may be going too fast. Large Language Models (LLM) are riddled with challenges which are yet to be addressed. It’s alright if one uses the technology knowing its limitations, checks citations Le Chat provides for example, but if the technology is pushed to people less familiar with it problems are sure to appear.

I still believe that real self-driving (not to be confused with Tesla’s Full Self-Driving (FSD) technology) has capacity to save lives. For example, as Timothy B. Lee observes, ‘most Waymo crashes involve a Waymo vehicle scrupulously following the rules while a human driver flouts them, speeding, running red lights, careening out of their lanes, and so forth.’ I also don’t think it’s inevitable that driverless cars will destroy cities as Jason Slaughter warns. [Added on 28th of March: citation of Lee’s article.]

But with AI systems finding their ways into more and more products, we need to tread lightly and test things properly. Otherwise, like Krzysztof in Kieślowski’s 1989 film Dekalog: One, we are walking on thin ice and insufficient testing and safety precautions may lead to many more failures.

1 The most amusing part of this case was that Air Canada claimed that the chatbot was ‘a separate legal entity that was responsible for its own actions.’ Clearly lawyers will try every strategy, but it’s also reminiscent of the case of ‘A Recent Entrance to Paradise’, I’ve discussed previously, where a computer was apparently doing work for hire. ↩

2 Having said that, the recent Tesla troubles remind me of another firm. WeWork cultivated an image of a technology company but under all the marketing, they were a property management company. Eventually, the realities of real estate caught up to them and the disruptor once evaluated at 47 billion dollars delisted its stock with a market cap of 44 million dollars. Similarly, Tesla was supposed to be more than just a car manufacturer. Once Elon Musk joined, he became the image of the company pushing it forward on the promise of disruptive technologies; but with time other firms caught up. Whatever happens, Tesla will likely survive, but maybe this is the beginning of the correction critics have been predicting for so long? ↩

Monday, 17 March 2025

Multi-OS Privilege Dropping in Go

After I started writing about techniques to let software drop privileges, I realized that there is way more to say than I first anticipated. To be able to finish the previous posts, I made many compromises and skipped some topics.

This became especially clear to me after finishing my last post on Privilege Separation in Go, which became very Linux-leaning. While I introduced common POSIX APIs and both Linux and OpenBSD APIs in the earlier Dropping Privileges in Go, only the Linux parts made it into the subsequent post.

The result was a post about architectural changes in software design to achieve privilege separation, but with examples only targeting Linux. Those examples were not portable, something I usually try to avoid. This post tries to make up for that and demonstrates how to write Go code with multiple OS-specific parts for different target platforms.

Non-Portable Code

But what exactly is non-portable code?

Let’s start with a very trivial example, calling OpenBSD’s unveil(2) via golang.org/x/sys/unix.

package main

import "golang.org/x/sys/unix"

func main() {

if err := unix.Unveil(".", "r"); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

if err := unix.UnveilBlock(); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

The problem is that the two functions unix.Unveil and unix.UnveilBlock are only defined for OpenBSD.

When building this program for other operating systems by setting the GOOS environment variable, it will fail.

$ GOOS=openbsd go build

$ GOOS=linux go build

# non-portable-example

./main.go:6:17: undefined: unix.Unveil

./main.go:9:17: undefined: unix.UnveilBlock

If there is code in the codebase that is restricted to certain operating systems, calling it will either fail, or the code will fail to compile, as just demonstrated.

Go Build Constraints

Go comes with an easy way to do conditional builds, including or excluding some files for certain targets. These are the so called build constraints.

They can be used by adding a build tag at the top of the Go file. A simple build tag restricting the file to OpenBSD looks like this.

//go:build openbsd

If only a few OS-restricted functions are involved, a new function that mimicks the original’s signature can be introduced. For the supporting OS, this function wraps the original function. Otherwise, it is either a no-op or raises an error, depending on the use case.

This pattern can be applied to the unveil(2) example above.

In an unveil_openbsd.go file, the original functions are being wrapped.

The same functions are then implemented in unveil_fallback.go, with an empty function body.

In the end, the main.go file now calls the mimicking functions instead of the originals.

// unveil_openbsd.go

//go:build openbsd

package main

import "golang.org/x/sys/unix"

func Unveil(path, permissions string) error {

return unix.Unveil(path, permissions)

}

func UnveilBlock() error {

return unix.UnveilBlock()

}

// unveil_fallback.go

//go:build !openbsd

package main

func Unveil(_, _ string) error {

return nil

}

func UnveilBlock() error {

return nil

}

// main.go

package main

func main() {

if err := Unveil(".", "r"); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

if err := UnveilBlock(); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

Building this modified version will work with the restriction enabled on OpenBSD, while still working unrestricted on any other operating system.

Abstraction Layer

This approach only scales so far. If there are multiple OS-dependent functions and the goal is to support multiple operating systems, this pattern will result in a lot of unnecessary stub functions that will eventually be forgotten.

There is an infamous theorem that any problem in software “engineering” can be solved by introducing another level of indirection. It is said that some even try to apply this to the problem of too much indirection itself.

Nevertheless, abstraction may save us here.

Instead of creating multiple shadow functions, a single function is introduced, having a lookup map to be populated by OS-specific implementations for all possible restrictions.

// Restriction defines an OS-specific restriction type.

type Restriction int

const (

_ Restriction = iota

// RestrictLinuxLandlock sets a Landlock LSM filter on Linux.

//

// The Restrict() function expects (multiple) landlock.Rule arguments.

RestrictLinuxLandlock

// RestrictOpenBSDUnveil sets and blocks unveil(2) on OpenBSD.

//

// The Restrict() function expects (multiple) string pairs like

// ".", "r", "tmp", "rwc". After calling unveil(2) for each pair of path and

// permission, unveil will be locked.

RestrictOpenBSDUnveil

)

// restrictionFns is the internal map to be populated for each operating system.

var restrictionFns = make(map[Restriction]func(...any) error)

// Restrict operating system specific permissions.

//

// Based on the Restriction kind, the variadic function arguments differ. They

// are described at their definition.

//

// Note, unknown or unsupported Restrictions will be ignored and do NOT result

// in an error. One may call RestrictOpenBSDUnveil on a Linux without any error.

func Restrict(kind Restriction, args ...any) error {

fn, ok := restrictionFns[kind]

if !ok {

return nil

}

return fn(args...)

}

The package-private restrictionFns map can be filled with multiple init functions, like the following.

//go:build linux

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/landlock-lsm/go-landlock/landlock"

)

func init() {

restrictionFns[RestrictLinuxLandlock] = func(args ...any) error {

rules := make([]landlock.Rule, len(args))

for i, arg := range args {

rule, ok := arg.(landlock.Rule)

if !ok {

return fmt.Errorf("landlock parameter %d is not a landlock.Rule but %T", i, arg)

}

rules[i] = rule

}

return landlock.V5.BestEffort().Restrict(rules...)

}

}

//go:build openbsd

package main

import (

"fmt"

"golang.org/x/sys/unix"

)

func init() {

restrictionFns[RestrictOpenBSDUnveil] = func(args ...any) error {

if len(args) == 0 || len(args)%2 != 0 {

return fmt.Errorf("unveil expects two parameters or a multiple of two")

}

for i := 0; i < len(args); i += 2 {

path, ok := args[i].(string)

if !ok {

return fmt.Errorf("unveil expects first parameter to be a string, not %T", args[i])

}

flags, ok := args[i+1].(string)

if !ok {

return fmt.Errorf("unveil expects second parameter to be a string, not %T", args[i+1])

}

if err := unix.Unveil(path, flags); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("cannot unveil(%q, %q): %w", path, flags, err)

}

}

return unix.UnveilBlock()

}

}

Eventually, an external caller can use this as follows.

func main() {

if err := Restrict(

RestrictLinuxLandlock,

landlock.RODirs("/proc", "."),

landlock.RWDirs("/tmp"),

); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("cannot filter Landlock LSM: %v", err)

}

if err := Restrict(

RestrictOpenBSDUnveil,

".", "r",

"/tmp", "rwc",

); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("cannot unveil(2): %v", err)

}

home, err := os.UserHomeDir()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("cannot obtain home dir: %v", err)

}

for _, dir := range []string{".", filepath.Join(home, ".ssh")} {

_, err := os.ReadDir(dir)

if err != nil {

log.Printf("cannot read dir %s: %v", dir, err)

} else {

log.Printf("can read dir %s", dir)

}

}

tmpF, err := os.Create("/tmp/08-multi-os-demo")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("cannot create temp file: %v", err)

}

if _, err := fmt.Fprint(tmpF, "hello world"); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("cannot write temp file: %v", err)

}

if err := tmpF.Close(); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("cannot close temp file: %v", err)

}

log.Print("created temp file")

}

Running the code produces the expected outcome.

2025/03/17 21:18:20 can read dir .

2025/03/17 21:18:20 cannot read dir /home/alvar/.ssh: open /home/alvar/.ssh: no such file or directory

2025/03/17 21:18:20 created temp file

Did Someone Say Abstraction Layer?!

While the calls to other operating systems are now harmless no-ops, there is still a distinction within the code. This looks like a textbook example for abstraction. For moar abstraction.

The existing structure already allows adding Restriction types independent of any operating system.

It was just the implementation so far that made them OS-dependent.

So another entry in the const-and-not-enum list may follow:

// RestrictFileSystemAccess is an OS-independent abstraction to limit

// directories to be accessed.

//

// The Restrict() function expects two string arrays, one listing directories

// for reading, writing and executing and a second one for reading and

// executing only.

RestrictFileSystemAccess

Its implementation can be built on top of RestrictLinuxLandlock and RestrictOpenBSDUnveil.

Both share the same type checking boilerplate and then call the underlying layer.

// Addition to the _linux.go implementation.

func init() {

restrictionFns[RestrictLinuxLandlock] = func(args ...any) error { /* ... */ }

restrictionFns[RestrictFileSystemAccess] = func(args ...any) error {

if len(args) != 2 {

return fmt.Errorf("RestrictFileSystemAccess expects two string arrays, not %T", args)

}

rwDirs, okRwDirs := args[0].([]string)

roDirs, okRoDirs := args[1].([]string)

if !okRwDirs || !okRoDirs {

return fmt.Errorf("RestrictFileSystemAccess expects two string arrays, not %T and %T", args[0], args[1])

}

return restrictionFns[RestrictLinuxLandlock](

landlock.RWDirs(rwDirs...),

landlock.RODirs(append(roDirs, "/proc")...))

}

}

// Addition to the _openbsd.go implementation.

func init() {

restrictionFns[RestrictOpenBSDUnveil] = func(args ...any) error { /* ... */ }

restrictionFns[RestrictFileSystemAccess] = func(args ...any) error {

if len(args) != 2 {

return fmt.Errorf("RestrictFileSystemAccess expects two string arrays, not %T", args)

}

rwDirs, okRwDirs := args[0].([]string)

roDirs, okRoDirs := args[1].([]string)

if !okRwDirs || !okRoDirs {

return fmt.Errorf("RestrictFileSystemAccess expects two string arrays, not %T and %T", args[0], args[1])

}

rules := make([]any, 0, 2*len(rwDirs)+2*len(roDirs))

for _, rwDir := range rwDirs {

rules = append(rules, rwDir, "rwxc")

}

for _, roDir := range roDirs {

rules = append(rules, roDir, "rx")

}

return restrictionFns[RestrictOpenBSDUnveil](rules...)

}

}

Finally, the two OS-specific Restriction(...) calls in the main function can be unified.

if err := Restrict(

RestrictFileSystemAccess,

[]string{"/tmp"},

[]string{"."},

); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("cannot restrict file system access: %v", err)

}

While this was not even my initial intent, this example of abstraction and unification shows both the advantages and disadvantages of the general idea.

On the plus side, a caller does not need to know any details about either Landlock LSM or unveil(2).

Under the hood, implementations for any other operating system can be added or replaced, and hopefully it will just work.

The trade-off is that the nuances of each implementation will be lost.

For example, unveil(2) explicitly allows or denies execution for each path, Landlock LSM does not.

Thus, the generalized API is reduced to the least common denominator of always allowing file execution, even if not necessary.

What To Use?

It is hard to say how many layers of abstraction to stack on another.

If the software only targets one operating system, nothing here matters - just let compilation fail on other platforms. Depending on the size of the software and the importance of portability, some level of abstraction will prove useful. Personally, I would mostly not attempt the last example of a unified API, since its generalized nature prevents access to specifics.

But again, it depends. And there are even other ways, using other technologies that were totally out of scope for this post.

For example, in the recent Go version 1.24, os.Root was added.

This is a Go API allowing to restrict file system calls going through it to be bound to a specific directory, described in more detail in Damien Neil’s “Traversal-resistant file APIs”.

While it does not restrict the whole process, it is easy to use without having to deal with the effects of the restriction in other places.

These features are not mutually exclusive, of course.

What to use now? Still depends.

However, if you just want the code shown in this post, look no further: codeberg.org/oxzi/go-privsep-showcase.

Sunday, 16 March 2025

1 + 2 + 3 + ⋯ = -1/12

This entry includes maths formulæ which may be rendered incorrectly by your feed reader. You may prefer reading it on the web.

In 2004, Brady Haran published the infamous Astounding: \(1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + \cdots = -\frac{1}{12}\) video in which Dr Tony Padilla demonstrates how sum of all natural numbers equals minus a twelfth. The video prompted a flurry of objections from viewers rejecting the result. But riddle me this: Would you agree the following equation is true: \[1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \cdots = 2\]

Obviously the equation does not hold. How could it? The thing on the left side of the equal sign is an infinite series. The thing on the right side is a real number. Those are completely different objects therefore they cannot be equal. Anyone saying the two are equal might just as well say \(\mathbb{N} = �\) (and while I grant you that elephants are quite large, they’re not sets of natural numbers).

And yet, people usually agree the infinite sum equals 2. Why is that? They use ‘mathematical trickery’ and redefine the meaning of the equal sign. Indeed, \(1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \cdots\) does not equal 2. Rather, given an infinite series \((a_n)\) where \(a_n = 2^{-n}\), we can define an infinite series \((S_n)\) where \(S_n = \sum_{0}^{n} a_n\) and only now we get: \[\lim_{n\to\infty} S_n = \lim_{n\to\infty} 2 - \frac{1}{2^n} = 2\]

But that’s a different equation than the one I’ve enquired about.

Historical perspective

Let’s consider some other mathematical statements:

- There exists a number such that adding it to 5 results in 4.1

- Square root of two cannot be represented as a ratio of two natural numbers.2

- There exists a number such that squaring it produces -1.3

- There are more real numbers than natural numbers.4

- Two parallel lines can intersect.5

All of those claims were at one point considered an ineffable twaddle; now they are intricately woven into the tapestry of modern mathematics and engineering. We shan’t be too harsh on our ancestors. We only need to think back to grammar school to understand their sentiments. One day we’re taught squaring produces a non-negative quantity; another we’re taught about imaginary numbers. Many a student has labelled complex numbers as nonsense. Yet, accepting them opens a wondrous universe of possibilities.6

In the video no one actually claims sum of all integers doesn’t diverge. But what if we assigned a number to it anyway? What if we allow for the equal signs to mean something different just like we allow square root of -1 to exist? Just as accepting non-Euclidean geometry opens up a whole new marvellous world to explore, what discoveries can we make if we use summation method which does say all integers sum to minus a twelfth?

School imparts people with the wrong idea of maths as a linear progression where all new discoveries mustn’t contradict what has been established already. But that’s not the case. It’s all made up and someone can come, make up other rules and see where those lead.

Rigour

Not everyone has an issue with assigning \(-\frac{1}{12}\) to the infinite series \(1 + 2 + 3 + \cdots\). Another criticism of the video is its lack of rigour. That I don’t disagree with as much. Indeed, the video could make it more explicit non-standard summation rules were used.

On the other hand, Numberphile (YouTube channel where the Astounding video has been published) is not a channel with academic lectures. Brady is a popular science communicator and his videos are not replacement for maths classes. For people interested in more rigour, Dr Padilla has published a supplementary article with a formal derivation.

Over the years Brady published other videos on the subject (many linked from his blog post which tries to calm the situation). It can be argued the video did decent job at popularising mathematics. I would certainly say, the amount of animosity still hurled at the video is unreasonable.

Generalities

I leave you with the following poem by Cyprian Kamil Norwid. It’s something my physics teacher made us learn by heart in high school. What does it have to do with physics? What does it have to do with Numberphile’s video? I leave it to your interpretation.

Generalities

Cyprian Kamil Norwid

When like a butterfly the Artist’s mind

In spring of life inhales the air,

It can but say:

‘The Earth is round — it is a sphere.’

But when autumnal shivers

Shake the trees and kill the flowers,

It must elaborate:

‘Though somewhat flattened at the poles.’

Amid the varied charms

Of Eloquence and Rhyme

One persists above the rest:

A proper word each thing to name!

Translation © All Peotry

1 Geometry had a big influence over early mathematics and negative quantities were considered absurd. Al-Khwarizmi, the guy whose book is the etymology of the word ‘algebra’, rejected negative solutions to quadratic equations. He also rejected negative coefficients in quadratics instead considering three separate equation ‘species’: \(ax^2 + bx = c\), \(ax^2+c=bx\) and \(ax^2=bx+c\). (See al-Khwarizmi, The Algebra of Mohammed ben Musa, edited and translated by Friedrich Rosen, Oriental Translation Fund, London, 1881). ↩

2 Legend has it that Greeks could be drown at sea for revealing the existence of irrational numbers. Perhaps a fitting end to someone who spread knowledge of the ‘inconceivable’! In reality probably just a metaphor but illustrated how Pythagoreans disregarded irrational numbers. (See William Thomson and Gustav Junge, The commentary of Pappus of Book X of Euclid’s Elements, Harvard University Press, 1930). ↩

3 We had to wait until 16th century until Gerolamo Cardano used what we now call complex numbers. As he laid out various rules for solving polynomial equations, square roots of negative numbers helped him find solutions to the problems. Even still, he called square roots of negative numbers ‘as refined as they are useless.’ (See Girolamo Cardano, The Great Art or The Rules of Algebra, edited and translated by T. Richard Witmer, The MIT Press, 1968). ↩

4 Proof that there are more real numbers than natural numbers is particularly late addition to mathematics. It was presented in 19th century by Georg Cantor who introduced concept of set cardinality. A work for which he received sharp criticism from his contemporaries. With time, some even suggested that contemplating the infinite drew Cantor mad, though there are no evidence his theories were source of his mental struggles. (See Joseph Warren Dauben, Georg Cantor: His Mathematics and Philosophy of the Infinite, Harvard University Press, 1979). ↩

5 The parallel postulate is the fifth postulate in Euclid’s Elements. It stands out for not being self-evident and throughout the centuries consensus among mathematicians was that the postulate was true but simply needed to be proven. It took over two millennia before independence of this postulate was discovered. (See Florence P. Lewis, History of the Parallel Postulate, The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 27, No. 1, 1920). ↩

6 Complex numbers found multiple uses in physics and engineering. But openness to them created opportunities for other benefits as well. For example, William Hamilton introduced quaternions which have three distinct numbers which all square to -1. They proved useful in computer graphics as representation of rotation. (See John Vince, Quaternions for Computer Graphics, Springer, 2021). ↩

Sunday, 09 March 2025

Mutable global state in Solana

Even though Bitcoin is technically Turing complete, in practice implementing a non-trivial computation on Bitcoin is borderline impossible.1 Only after Ethereum was introduced, smart contracts entered common parlance. But even recent blockchains offer execution environments much more constrained than those available on desktop computers, servers or even home appliances such as routers or NASes.

Things are no different on Solana. I’ve previously discussed its transaction size limit, but there’s more: Despite using the ELF file format, Solana Virtual Machine (SVM) does not support mutable global state.

Meanwhile, to connect Solana and Composable Foundation’s Picasso network, I was working on an on-chain light client based on the tendermint crate. The crate supports custom signature verification implementations via a Verifier trait, but it does not offer any way to pass state to such implementation. This became a problem since I needed to pass the address of the signatures account to the Ed25519 verification code.2

This article describes how I overcame this issue with a custom allocator and how the allocator can be used in other projects. The custom allocator implements other features which may be useful in Solana programs, so it may be useful even for projects that don’t need access to mutable global state.

The problem

The issue is easy to reproduce since all that’s needed is a static variable that allows internal mutability. OnceLock is a type that fits the bill.

fn process_instruction(

_: &Pubkey,

_: &[AccountInfo],

_: &[u8],

) -> Result<(), ProgramError> {

use std::sync::OnceLock;

#[no_mangle]

static VALUE: OnceLock<u32> = OnceLock::new();